There’s something quietly rebellious about walking out of a used bookstore with an armful of paperbacks. Not first editions or collector’s items—just books that have survived somebody else’s dorm room, somebody else’s nightstand, somebody else’s life. In a time when entire libraries can vanish with a few keystrokes, buying physical books feels like an act of resistance.

I used to think the Kindle was liberation. A thousand books in my pocket, every title available instantly. I was an early adopter and immediately saw that physical books were going to join the other analog media that I had been quietly getting rid of since the early 2000s. But digital libraries aren’t libraries; they’re leases. You don’t own what’s on your Kindle. Amazon does.

I learned that the hard way. When the Fellow Travelers miniseries came out, the Kindle edition of the novel vanished—and so did the copy I’d already bought. Not “unavailable,” not “temporarily removed.” It was gone. The cover disappeared from my library, and even my Amazon order history showed nothing. For weeks it was as if I’d imagined the whole thing. Then it quietly reappeared under a new tie-in edition, ready to be bought again.

It’s back now, of course. But that almost makes it worse. Stories shouldn’t blink in and out of existence without explanation. The glitch passed, but the message stayed: a digital bookshelf can be rewritten at any moment.

And I don’t think it would take much—one phone call, one email from the right office—for a book to disappear. George Orwell’s 1984, of all things, once vanished from Kindles overnight because of a licensing dispute. The idea that a government—or a corporation—could erase a title isn’t dystopian anymore; it’s customer service. One click, and the bookshelf is clean.

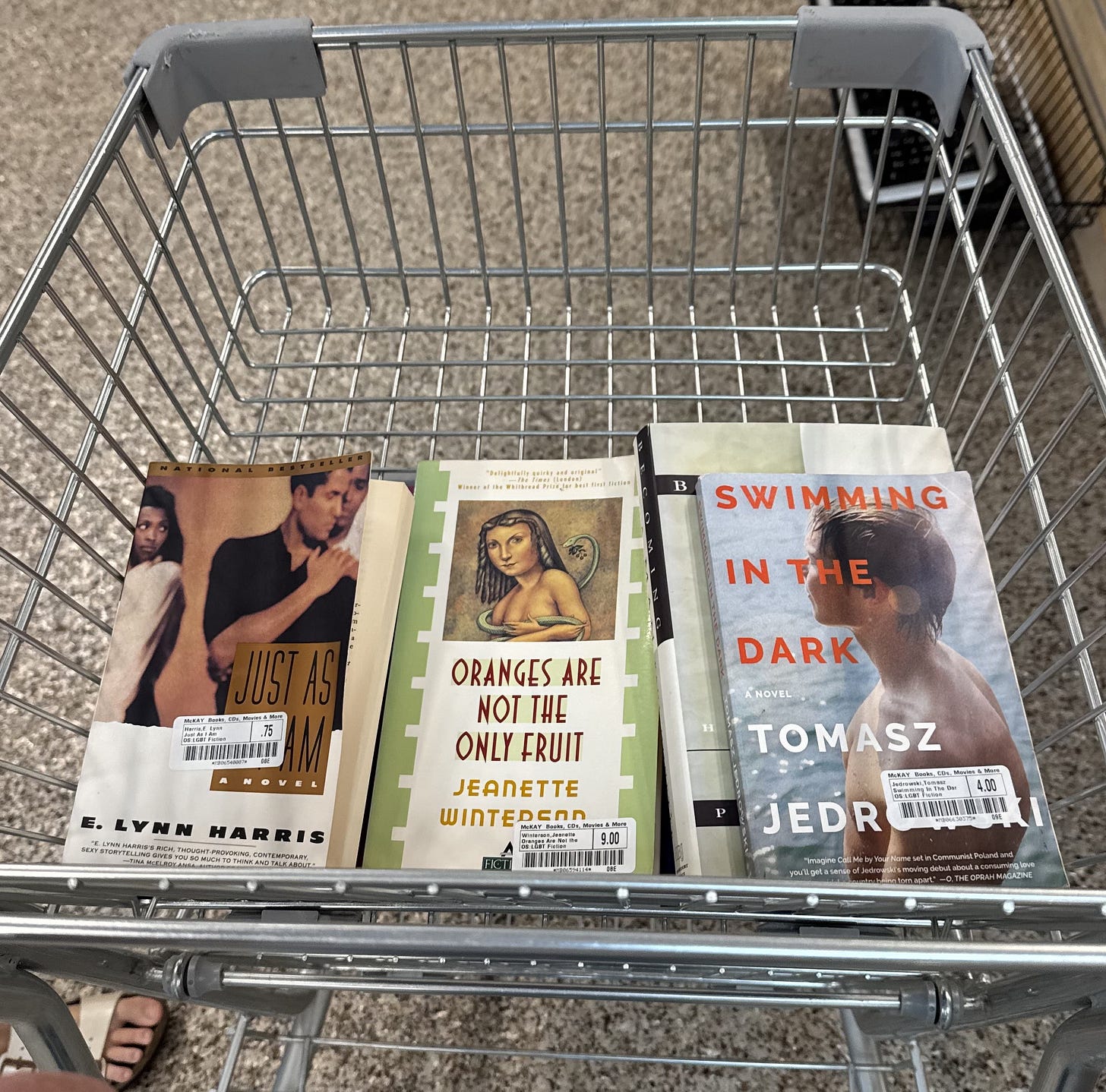

So I’ve started buying the things I can hold.

McKay’s and the Box Set That Started It

I first wandered into a McKay’s used books in Knoxville, TN years ago and left with the complete Twin Peaks box set—a gift, technically, but really a calling. McKay’s is a regional chain with locations in TN and NC. Each store is a fluorescent labyrinth where college kids sell everything they got for Christmas the minute they get back to campus, and the rest of us go to buy back the physical media we’d sworn off. Every aisle smells faintly of dust and déjà vu.

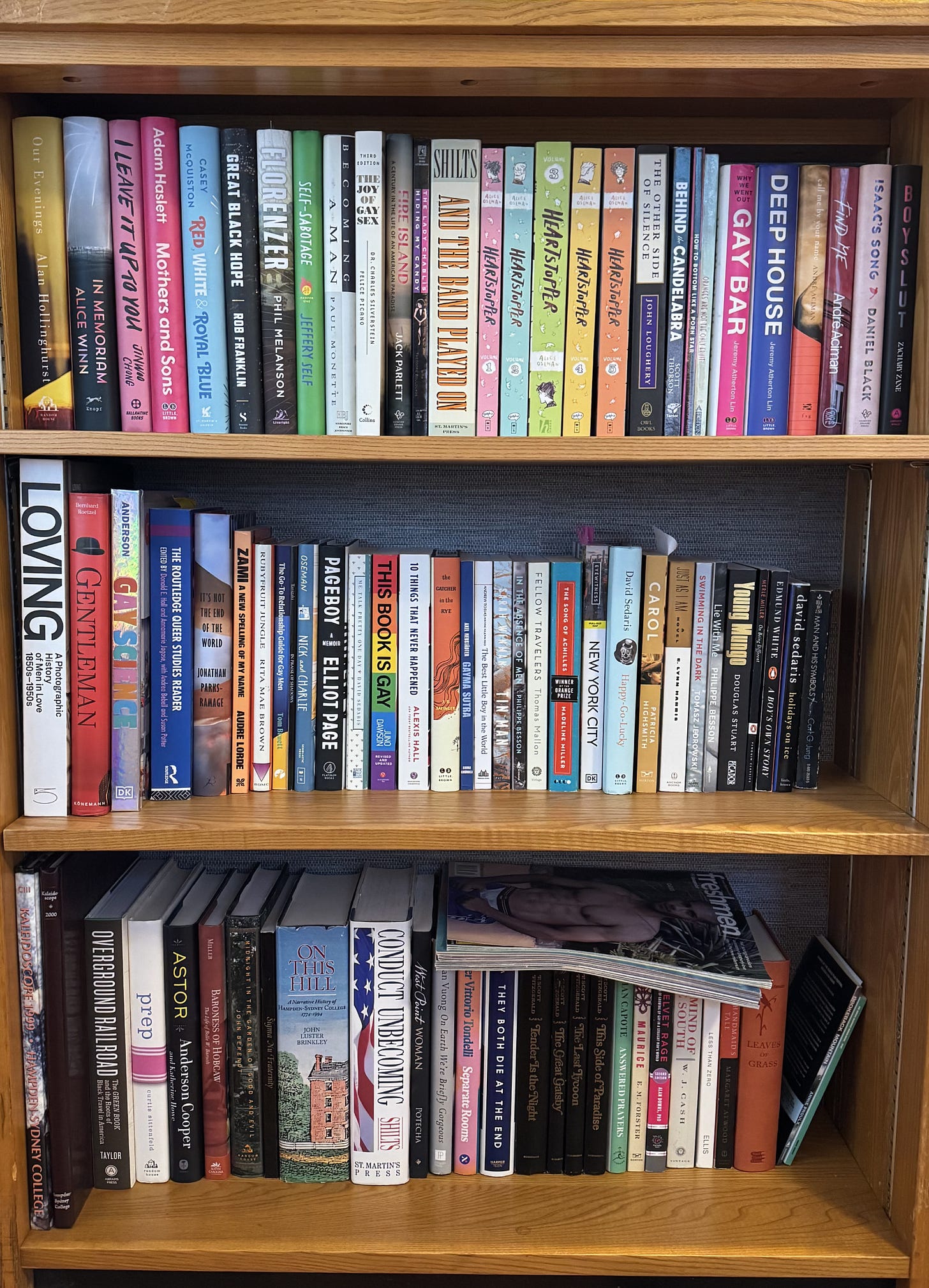

When David Lynch passed away earlier this year, I thought back to that box set, and sat down to rewatch the series. It felt like handling a sacred relic—grainy, electric, unsettling in all the right ways. No digital enhancement, it looked and sounded exactly as it did when the show originally aired on ABC in 1991. Streaming would have sanded off its edges; the DVD made them unavoidable. That was the moment I realized: you can’t count on the cloud to preserve the weird, the daring, or the banned. You have to keep your own archive.

The 22-Point Rebellion

I’ll admit it’s not as easy as it used to be. My eyes have joined the protest. Now I read with thick glasses instead of bumping the Kindle font up to 22-point—the size where three sentences fill the screen and everyone on the plane can read along with me. From behind, I probably look ridiculous: hunched over a paperback, head tilted toward the lamp. But I don’t care. Every page I turn feels like proof that I still own something no algorithm can resize or remove.

The Late Arrival

The strangest part of all this is discovering it at forty-five. Not as a teenager sneaking a paperback into my book bag, but as an adult with an education and decades of hindsight. Reading and watching now isn’t about rebellion; it’s about recognition.

When I finally opened Giovanni’s Room, I didn’t feel like a latecomer—I felt like someone who had finally learned the language for feelings I’d been translating my whole life. Coming to these works with forty-five years of lived experience is different. You see what they were really saying. You see yourself, and it’s both heartbreaking and electric.

The Fear That Follows

That’s what really scares me—not losing access for myself, but imagining some fifteen-year-old out there trying to find comfort in the same stories I denied myself and finding nothing. The titles have been pulled, the pages quarantined under “review,” the files deleted. I keep buying these books now because I want them to exist somewhere—on a shelf, not a server. Within reach of whoever needs them next.

Banned Books Week

This week happens to be Banned Books Week, which feels almost too on the nose. Even Bookshop.org emailed out a list of their most challenged titles, complete with ISBNs and a 20 percent discount code. I’ll have my own checklist as a free download below, but I’m also setting up a separate Bookshop shelf for anyone who wants to browse those same banned books directly and support indie stores in the process.

I’m forty-five and finally reading what I should have read at twenty. Watching what I was scared to watch. Holding the things that once made other people uncomfortable and realizing they make me whole. That’s reason enough to build a library you can touch.

📘 Download the full checklist:

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

🧵 Join me on Threads: Caleb_Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

So well articulated! I am on this same journey. Both away from digital content for the media that is most at risk and by connection the building of the physical library I never had and undervalued when younger.

I look forward to seeing your collection grow and for a future piece on magazines as I’ve been moving in that direction as well.