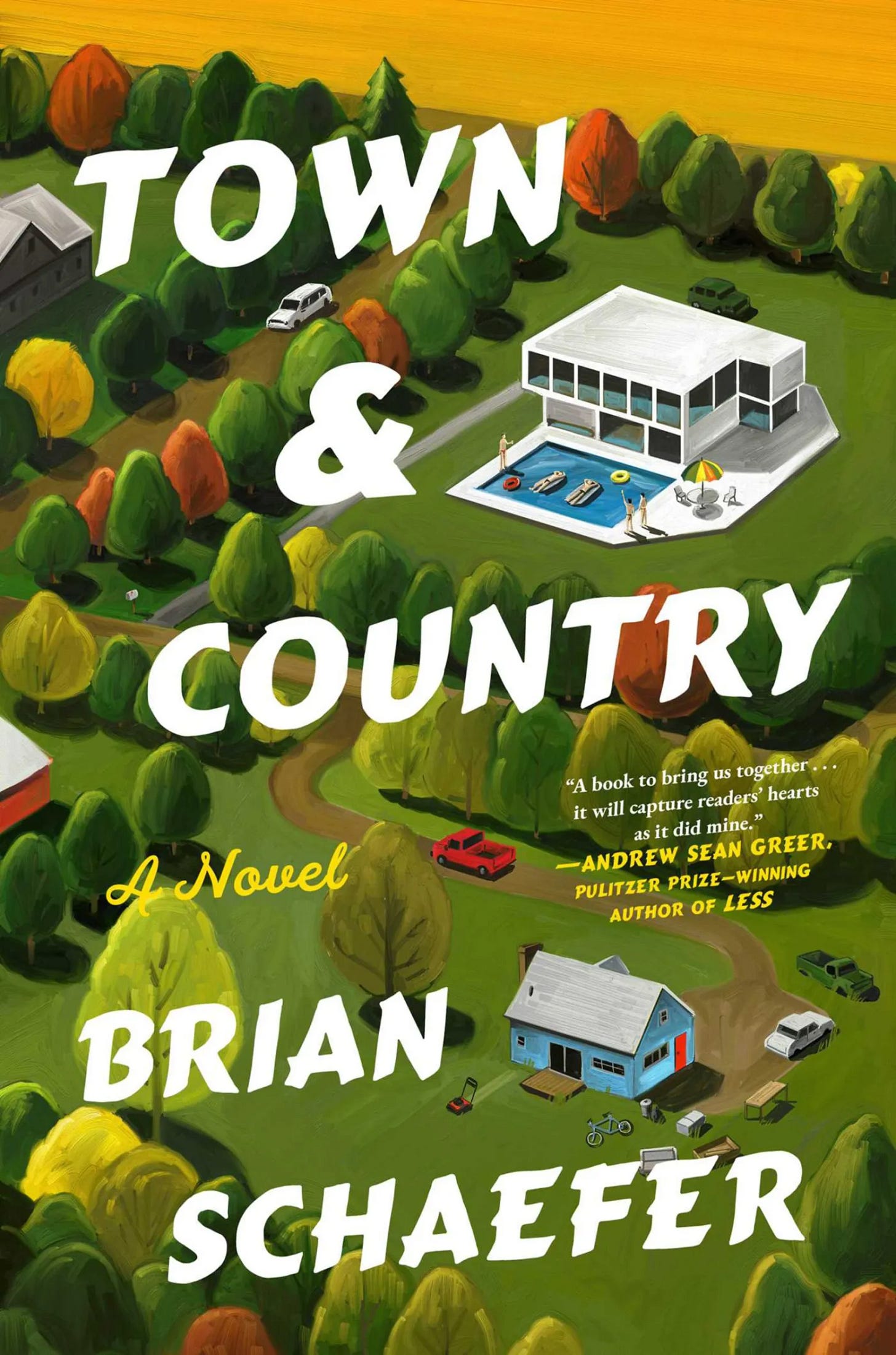

There’s something quietly reassuring about a title like Town & Country. It promises order before you even open the book. Two places. Two ways of being. A sense that life might still sort itself into recognizable shapes if you choose correctly.

That promise matters more than it probably should. We’re living in a moment when very little feels settled. Identity, work, community, even home all feel provisional now, as if they could shift beneath you at any moment. A clean binary, even a false one, can feel like relief.

Brian Schaefer’s novel understands this impulse. It’s a quiet book, deliberately so. Nothing explodes. No one makes a grand speech that reorganizes the room. Instead, the story unfolds through atmosphere, small interactions, and the steady accumulation of unease. You’re asked to notice how people move through their lives rather than what they accomplish inside them.

The divide between town and country isn’t really about geography. It’s about the fantasy that somewhere else exists a version of life that would feel more coherent. The town carries performance, proximity, the sense of always being observed. The country offers distance, silence, the hope that you might finally loosen your grip on who you’re expected to be. Neither place quite delivers. But the desire to choose between them remains powerful.

That tension is most clearly embodied in Will. His coming out is not treated as a dramatic turning point, and that choice feels intentional. There’s no neat before and after. Instead, disclosure becomes the beginning of a longer, more uncomfortable process: how to exist more honestly without becoming newly exposed, how to be seen without being defined entirely by what has been revealed.

Will’s tentative connection to the Duffels captures this beautifully. The group offers something he wants badly: community, structure, a sense of belonging that doesn’t require explanation. But even here, belonging comes with conditions. The novel is attentive to how community can feel both sheltering and restrictive, especially for someone still learning where the edges of the self lie.

There’s something painfully familiar in this. Coming out doesn’t automatically solve the problem of loneliness. It often sharpens it. You trade one form of invisibility for another, learning that acceptance can still carry expectations, and that being welcomed doesn’t always mean being fully known.

Schaefer’s prose mirrors this emotional landscape. It’s restrained, careful, often holding feeling just short of full expression. That restraint doesn’t feel cold. It feels protective. As if the book understands how risky it can be to say too much, to want too much, to ask for clarity the world may not be able to offer.

This places Town & Country firmly within a broader strain of contemporary fiction that favors the small and the contained. Limited casts. Modest stakes. Interiors rather than events. These novels don’t try to diagnose the entire culture. They focus instead on how it feels to live inside it. In a world that often feels too loud, this kind of attention can feel like mercy.

At the same time, the novel gestures quietly toward questions of class and mobility. Town and country are not equally available choices, and the freedom to move between them carries its own privilege. Schaefer never presses this point aggressively. Sometimes the tension dissolves back into atmosphere. But the discomfort lingers, which may be the point.

There’s also an unavoidable political undercurrent to the town-and-country divide, one the novel gestures toward without fully interrogating. The ability to move “to the country” is rarely neutral. It often arrives with money, with taste, with the quiet confidence that one’s presence will be welcomed or at least tolerated. What gets described as escape can look, from another angle, like displacement. Rural spaces become aesthetic backdrops for urban exhaustion, shaped to meet the emotional needs of newcomers while long-standing communities absorb the cost. Schaefer doesn’t make villains of this dynamic, but its shadow lingers. The country promises authenticity and relief, yet that promise is often built on uneven ground.

What stays with me most is the sense of suspension. Will exists between versions of himself, between places, between communities. The novel refuses to rush him toward resolution. The town never entirely releases its hold. The country never fully redeems. Even the Duffels offer connection without certainty.

That feels honest. Most of us don’t arrive cleanly at the lives we imagine for ourselves. We circle them. We test them. We stand halfway inside one world while still feeling the pull of another.

In that way, Town & Country delivers something more complicated than its title suggests. The comfort isn’t in choosing one side or the other. It’s in recognizing how many of us are living in the in-between, trying to build meaning without the reassurance of clear borders.

The binary promises clarity. The novel offers recognition. And right now, that may be the more generous gift.

Editor’s note: I first encountered Town & Country through Jerry Portwood’s interview with Brian Schaefer, which I listened to before reading the novel itself.

The book was also a recent selection of Eric Cervini’s Very Gay Book Club, situating it within a wider, thoughtful conversation that feels very much in keeping with its tone.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: Caleb Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

🦋 Bluesky: @thecalebreed.bsky.social

Thanks so much, Caleb (and Jerry)! This is so beautiful and insightful.

so glad I could help with the discovery of this novel!