In an essay last week, I wrote about The Great Gatsby—about Robert Redford, the green light, and my mother’s old Scribner set that sat like a monument on the bookshelf of my childhood home. Gatsby was the Fitzgerald everyone knew, the one teachers assigned and movie stars embodied. It was the novel I inherited, the glittering story I was told was important before I was even old enough to read it.

But Gatsby was never the Fitzgerald who felt like mine.

That distinction belongs to This Side of Paradise, his first, unruly novel. If Gatsby was the book I was given, Paradise was the book that claimed me. Where Gatsby dazzled with polish, This Side of Paradise sprawled with rawness. Where Gatsby mythologized, Paradise confessed. And in Amory Blaine, Fitzgerald gave me a character I didn’t just study—I identified with, uncomfortably and completely.

Published in 1920 when Fitzgerald was just twenty-three, This Side of Paradise isn’t tidy. It lurches from prose to poems to playlets to long passages that feel like diary entries disguised as fiction. It reads like a young man trying everything at once, desperate to be noticed, to matter. And it worked—overnight it made Fitzgerald famous, and by extension, it convinced Zelda Sayre he was worthy of her.

But what stayed with me wasn’t the acclaim. It was Amory Blaine: spoiled, arrogant, endlessly self-mythologizing, convinced of his own brilliance—and underneath it all, deeply insecure. He reinvents himself constantly, trying on roles like costumes: the romantic, the cynic, the striver. None fit for long. By the novel’s end, he isn’t triumphant. He isn’t ruined, either. He’s stripped bare, facing himself without disguise.

That was the first time literature held up a mirror to me.

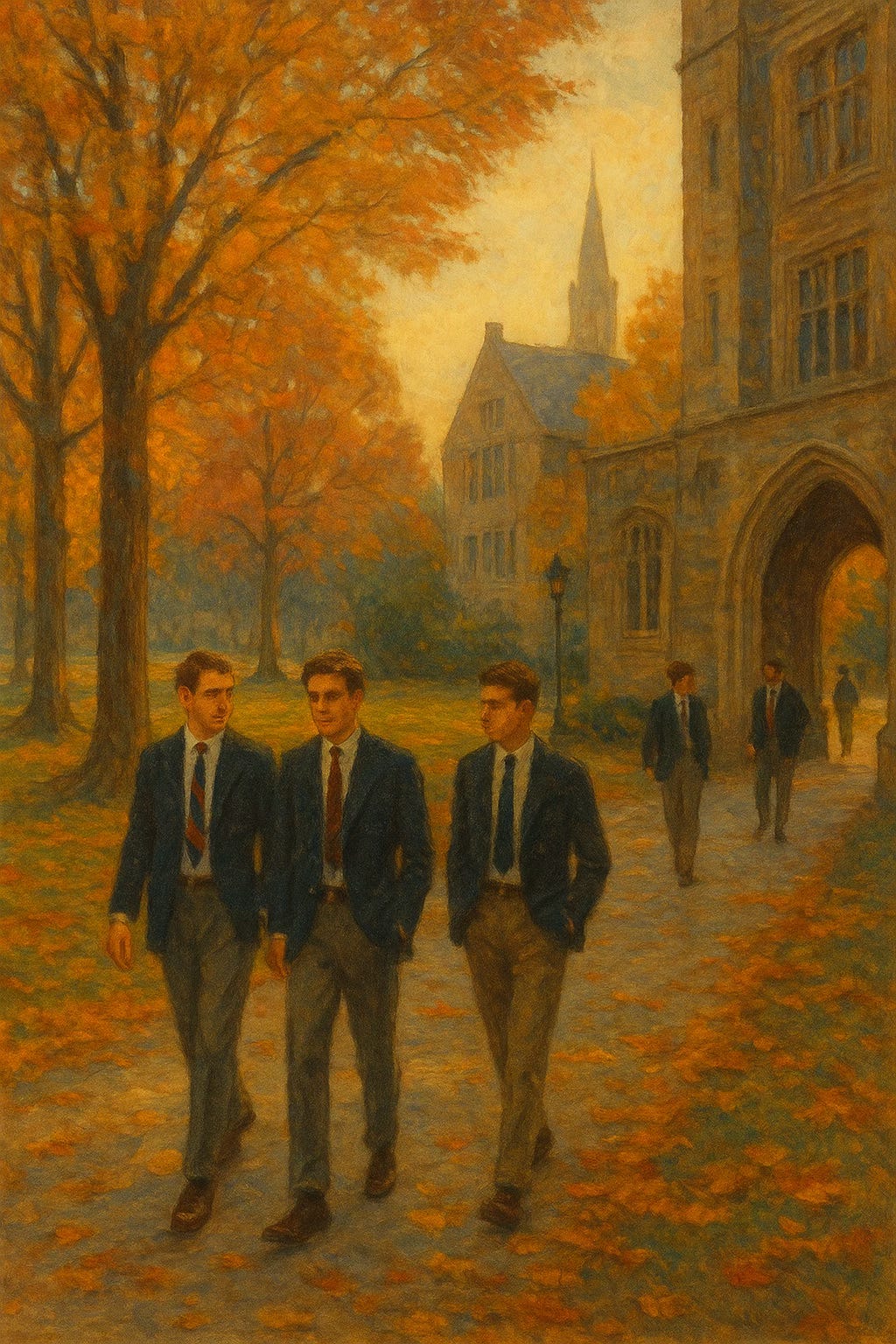

As a teenager, I devoured boarding-school movies like Dead Poets Society and School Ties. They carried the electricity of young men living together: blazers and dorms, whispered rivalries, midnight laughter spilling down hallways. For many of us, they were a gay awakening. The young stars Ethan Hawke, Brendan Fraser, Matt Damon —became the faces of a thousand first crushes. Wil Wheaton even jokes about how many gay awakenings he was responsible for, and Keith Coogan posted about School Ties just today on Instagram. They knew exactly what they were doing: casting beautiful, vulnerable boys in stories about identity, loyalty, and exposure.

In School Ties Matt Damon’s hostility toward Brendan Fraser’s character seems rooted in jealousy, class insecurity, and rivalry. But beneath that, there’s an unmistakable undercurrent of something more complicated—an intensity of fixation, resentment, and perhaps unrecognized attraction. The infamous shower scene in School Ties wasn’t just plot; it was recognition. The fear of being found out, the rivalry charged with intimacy. The same tension hums in Amory—the dread of exposure, the ache to belong, the pulse of being seen.

It wasn’t taboo; it was atmosphere. The smell of sweat, dirty laundry, wet towels and cologne. Beer hidden under beds, cigarette smoke drifting out windows. I could feel the current of living with young men in close quarters, where everything was competition and intimacy.

That’s the energy Amory spends an entire novel chasing—not sex, exactly, but recognition. The thrill of mattering in a world where everyone auditions for a role.

When I went to college, I didn’t end up at Princeton like Amory but at a small, all-male college in Virginia. Belonging there, as in Paradise, was performance: which fraternity you pledged, how you dressed, how you carried yourself. I built a story about who I was supposed to be and tried to live up to it. On the surface it looked like confidence; inside it felt like acting.

That was Amory too. Fitzgerald himself wasn’t much different—a boy from St. Paul who never quite fit at Princeton, watching the well-born glide through life with ease, desperate to belong. This Side of Paradise was his ticket in. It bought him celebrity and Zelda, but the novel is clear-eyed about the emptiness of it all.

By the final pages, Amory isn’t celebrated; he’s exhausted. His illusions have fallen away. The things he thought would make him exceptional—his looks, wit, ambition—aren’t enough. All he’s left with is honesty.

That honesty landed harder than Gatsby’s grandeur ever did.

Atmosphere as Memory

Rereading This Side of Paradise, what I notice most isn’t plot but atmosphere. Fitzgerald doesn’t dwell on it, but the scent is there: cigarettes and sweat, wool blazers worn too many humid nights, books thumbed by countless hands.

That smell was the background of my youth, a mirror I couldn’t look at directly. Like Amory, I thought I chased tradition, legacy, success. What I really sought was recognition: the desire to be seen, to matter, to be chosen.

Masks and Mirrors

Amory’s greatest fear is ordinariness. Mine was being found out.

I wasn’t the alpha male. I wasn’t the smooth, confident guy everyone admired. I was the kid pretending. Every day felt like a test of whether I could pass. Despite objective evidence—grades, scholarships, leadership—I lived as if it could collapse at any moment if someone noticed I didn’t truly belong.

That’s why Amory mattered to me. Vain, flawed, insufferable, he was also real. His masks were my masks. Fitzgerald didn’t give him a tragic grandeur or heroic arc. He gave him what I recognized: the exhaustion of pretending, the stripping away of illusion, the faint hope of starting over honestly.

Reading It Again

Now, rereading This Side of Paradise, I see Amory and Fitzgerald differently—not as arrogant young men but as boys announcing their pain. And I see my nineteen-year-old self in their pages: closeted, anxious, performing belonging, desperate to be chosen.

The book has become a time capsule. It reminds me that belonging built on performance never lasts. Masks slip, and when they do, you’re left with yourself.

That’s why This Side of Paradise remains my favorite Fitzgerald novel. It isn’t perfect—it’s messy. But that mess is what makes it honest.

References & Links

This Side of Paradise — F. Scott Fitzgerald (Amazon) or (Bookshop.org)

The Great Gatsby — F. Scott Fitzgerald (Amazon) or (Bookshop.org)

Dead Poets Society (1989 film) — original screenplay by Tom Schulman, later novelized

School Ties (1992 film) — original screenplay by Dick Wolf (Law & Order) and Darryl Ponicsan

Stay Connected

🌐 Subscribe: thecalebreed.com

📚 Bookshop shelf: The Reading Behind Line & Verse

📸 Instagram: @caleb_writes

🐦 X/Twitter: @CaleBreed_story

👍 Facebook: Caleb Reed

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but it helps support my work

Amazing insight on your part. Being able to mirror so much outside of self is deep. Your prose are the best and your self exposure is truly an unexpected truth.