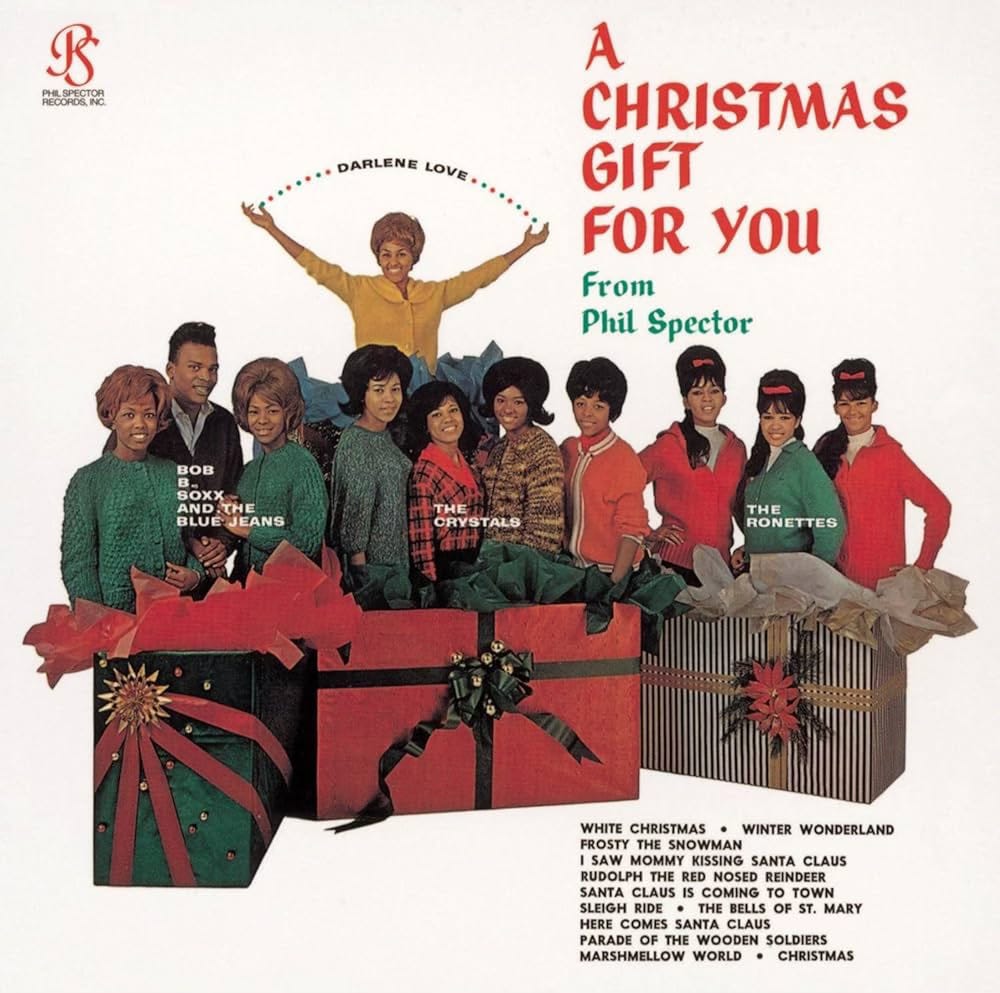

The Wall of Sound, Darlene Love, and the Last Great Christmas Spectacle

A love letter to maximalism, longing, and the holiday ritual we’ll never see again.

There’s a moment every December (or sometimes October) when the season finally begins for me. Not when the tree goes up, not when the temperatures drop, but in the instant those first driving notes of “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” burst through the speakers. Nothing else comes close. Not the crooners, not the hymns, not the curated holiday playlists designed to smell like a scented candle.

It’s Darlene Love — that voice, that ache, and that impossible wall of sound behind her — that signals the shift into Christmas.

The history is complicated. Phil Spector was a visionary producer, yes, but also a violent, paranoid man who eventually became a murderer. There is no separating the brilliance from the destruction. Yet the music remains, because its emotional force didn’t come from Spector’s control. It came from the human beings whose voices and labor filled those rooms — most of all, Darlene Love herself.

To understand why this song still lives at the center of the season, and why the final Letterman performance has become its own form of secular liturgy, you have to go back to the beginning. To the rooms where the music was physically built. To the woman whose voice could overpower an entire production apparatus. And to one claymation parody that, against all odds, treated the tradition with absolute sincerity.

This is the story of maximalism, longing, and the strange lineage of American Christmas music — a lineage that begins with bodies packed into a studio and ends, fittingly, on the stage of one of the last great temples of television spectacle.

Rooms Filled with People: The Physics of Early Pop

Before stereo.

Before multitrack recording.

Before digital layering.

Before a single producer in sweatpants could build a cathedral of sound on a laptop.

If you wanted a bigger record in the early 1960s, you didn’t reach for plugins. You reached for people.

More guitars playing the same line in unison.

More drummers driving identical rhythms.

More pianos stacked on top of one another.

And, crucially, more singers — the Spectorettes — to create that massive, shimmering choral blend.

The Wall of Sound wasn’t an abstraction. It was manpower. It was bodies generating air pressure in a confined studio until the tape could barely hold the energy. That is why the records overwhelm you. They were built to overwhelm you.

And then Tina Turner arrived — the clearest proof that one human voice could rival the machinery built to amplify it.

Tina Turner and the Human Wall of Sound

There’s a moment in What’s Love Got to Do with It that captures something essential about Tina Turner’s early career. She’s putting on her makeup backstage before a performance. Phil Spector watches her through the mirror. The film plays it as subtle, almost playful, but beneath it is a harsher truth: it’s the first time a powerful man in the industry says to Ike Turner, implicitly, what Ike feared most:

“No. I only want her.”

Not the revue.

Not the brand.

Not the choreography or the structure that Ike controlled.

Just Tina.

You can see the realization flicker across Ike’s face. Someone with musical authority has named what everyone already knows: Tina Turner is the gravitational center of the act.

Spector may have been unstable and, ultimately, dangerous, but he understood instantly that Tina didn’t need the machinery he built. She didn’t need the Spectorettes or the stacked guitars or the echo chamber at Gold Star Studios. She didn’t need a wall of sound.

Because she was one.

You hear this with full clarity on “River Deep, Mountain High.” Spector threw his entire sonic arsenal at the track — the orchestra, the choir, the roaring percussion — and Tina still rises above it like a supernova. It’s the moment the system admits what it cannot contain: one voice can overpower the architecture meant to support it.

The record flopped in the U.S.

Spector unraveled.

Tina moved forward.

But the truth of that recording remains: it is the clearest demonstration of what happens when human force eclipses technological aspiration.

“Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” and the Architecture of Longing

If Tina was the voice that transcended the system, Darlene Love was the voice that gave it emotional depth.

Spector undermined her career repeatedly — shelving recordings, controlling release schedules, burying tracks — but none of that diminishes what’s on tape. “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” is one of the great feats of American pop: a heartbreak song disguised as a holiday anthem, longing wrapped in tinsel and bells.

It’s the sound of someone calling out into winter air, hoping someone is listening.

The arrangement is enormous — the definitive Wall of Sound — but the core is intimate. She’s singing to one person who isn’t there. That tension is why the song returns every December. It’s not nostalgia. It’s emotional truth.

And it’s why David Letterman turned it into an annual tradition.

And why Paul Shaffer escalated the arrangement every single year.

Until, finally, it became the last great televised Christmas spectacle.

But before we get there, there’s the strangest, most affectionate homage of all: a claymation fever dream with more musical integrity than most Christmas specials.

The Claymation Interlude: SNL’s “Christmastime for the Jews”

In December 2005, Saturday Night Live aired one of Robert Smigel’s most memorable TV Funhouse shorts: “Christmastime for the Jews.” Stop-motion claymation, Rankin/Bass visual language, and a parade of New York Jewish life dialed to absurdity.

But the key is the music.

Darlene Love sings the track herself — not a sound-alike, not a parody vocalist, but Darlene Love. The arrangement is a meticulous recreation of the Spector-era Wall of Sound: real horns, real choir, real stacked vocals.

It works because the music is treated with total seriousness.

The parody lands only because the sonic architecture is legitimate.

You cannot spoof the Wall of Sound unless you build the Wall of Sound.

The sketch is affectionate, ridiculous, and unexpectedly faithful — and it forms a bridge between the original Christmas album and the modern cultural memory of it.

Which brings us to the stage where the tradition would find its last, greatest incarnation.

The Letterman Years: Ritual, Excess, Economics, and the Last Great Live Wall of Sound

For more than twenty years, Darlene Love appeared on the Late Show with David Letterman to sing “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home).” Over time, it became its own form of liturgy — the unofficial opening ceremony of the season.

Paul Shaffer approached the arrangement with escalating ambition.

Every year: bigger.

Every year: fuller.

Every year: more.

And this is the part younger viewers can’t fully grasp:

this spectacle was only possible because of the economics of an earlier era of television.

Before streaming hollowed out revenue.

Before cord-cutting decimated ratings.

Before the Big Three networks lost their monopoly on national attention.

In those years, late-night shows could afford enormous live arrangements: union musicians, horn sections, string sections, dancers, staging rigs, snow machines, and elaborate lighting resets — all for a four-minute performance.

Today, a host can be number one in late-night and still not turn a profit. The ecosystem that funded this kind of spectacle no longer exists.

Which is why these performances — and especially the final one — feel like the last of their kind.

And then there’s the space itself.

All of it happened in the Ed Sullivan Theater — the last great American broadcast room built for this kind of scale. The stage where the Beatles first played. Where orchestras performed weekly. Where variety shows once dominated the medium.

It is a room designed for spectacle.

When Darlene Love tore into “Please… come home” that final night in 2014, she wasn’t singing into a typical late-night studio. She was filling one of the defining theatrical spaces of twentieth-century television.

By then, the production had tipped into full-on Christmas opera:

snow machines fanning the stage

dancers swirling in choreographed chaos

an expanded choir filling the rafters

strings and horns crowded into every corner

And in one of the earlier years, a saxophonist was even lowered from above — a visual embodiment of the “answering voice,” the long-acknowledged musical stand-in for the absent lover in the song. A metaphor made literal.

It is theatrical.

It is excessive.

And it is perfect.

This is what camp truly is: sincerity expressed through grandeur, emotion rendered through scale. The Letterman tradition became one of the most fully realized pieces of queer-adjacent holiday camp ever broadcast on network television — not because it was silly, but because it was emotionally enormous.

And then comes the moment that seals its place in history.

After the last note of the final performance, David Letterman — famously resistant to overt sentiment — stands up from behind his desk, crosses the stage, shakes Paul Shaffer’s hand, and gently kisses Darlene Love’s hand as she stands on the piano.

He almost never did that.

But for this moment, for this tradition, he broke character.

It was the acknowledgement of something ending:

not just a yearly performance, but the economic, cultural, and architectural world that made it possible.

Why This Music Endures

So why does all of this still resonate? Why does this tradition stay lodged so firmly in the cultural imagination? Why does “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” remain, for so many people, the true start of the holiday season?

Because the Wall of Sound wasn’t merely a production style.

It was a way of turning longing into architecture.

A way of building a container big enough to hold an oversized feeling.

A way of giving emotional excess a physical form.

Christmas is the one season where that scale feels appropriate.

Where longing, memory, distance, joy, and ache coexist in equal measure.

Tina Turner proved the machinery wasn’t necessary.

Darlene Love gave it heart.

Robert Smigel revealed its strange joy.

Paul Shaffer rebuilt it every December with reverence.

And Letterman — despite himself — let the spectacle move him.

The final performance stands as the last great moment when network television had both the resources and the audacity to stage something on that scale. It is the end of an era when “big” was possible.

And the Wall of Sound endures not because of the man who invented it, but because of the artists who transformed it into something deeper, more human, and more lasting than he ever imagined.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

🦋 Bluesky: @thecalebreed.bsky.social