A Little Life - Hanya Yanaglhara

The Outsiders Wound: On A Little Life and the problem of borrowed suffering

I don’t usually read eight-hundred-page novels about other people’s pain. But back when I was driving eighty miles a day for hospital work, Audible became my companion. After a dozen books, its algorithm seemed to know my taste better than I did. One morning it queued up a title I’d never heard of—A Little Life.

The blurbs were glowing, the cover was striking, and everyone called it the great modern gay novel. Matt Bomer was even the narrator. It had everything.

So I listened—all eight hundred brutal, exhausting pages. When I finished, I felt stunned, almost reverent. Then I learned that none of it was real. The story wasn’t drawn from anyone’s life; it was wholly invented by a straight woman who later said the characters’ sexuality was “incidental.”

That revelation changed everything. What I’d taken as witness suddenly felt like reenactment.

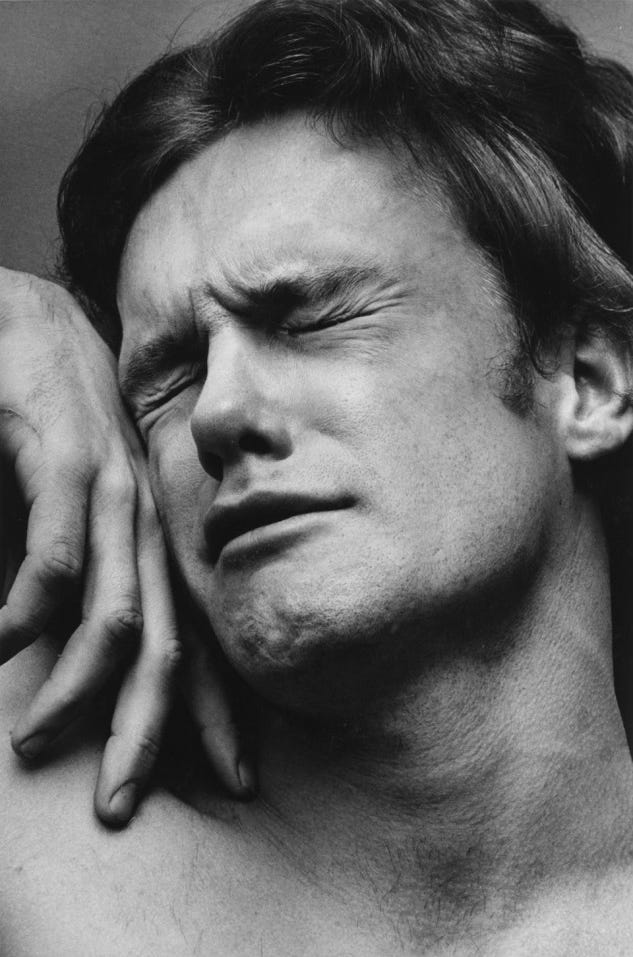

If queerness was incidental, then why is Peter Hujar’s Orgasmic Man—one of the most iconic photographs of gay desire—on the cover?

The photograph that fooled me

I honestly thought it was Matt Bomer on the jacket—how could I not? The expression, the bone structure, the intimacy. It looked like a publicity shot from the audiobook itself. Only when I sat down to write about it did I realize how wrong I was.

Orgasmic Man was taken in 1969 by Peter Hujar, a photographer who chronicled New York’s queer underground long before it was safe to be visible. Hujar’s portraits captured the vulnerability of drag performers, lovers, and friends in a community later decimated by AIDS. His images are devotional, not voyeuristic—windows into private worlds that most of the world ignored.

The man in the photo is artist and activist David Wojnarowicz, caught mid-ecstasy, head thrown back, eyes closed. It isn’t just erotic; it’s defiant—a moment of joy wrested from a hostile world. Hujar died of AIDS in 1987. His work now stands as testimony, a record of queer life lived on its own terms.

So discovering that this photograph graces the cover of a novel written by someone who described her characters’ sexuality as “incidental” felt jarring. The image carries decades of history; the story inside, none.

That realization became my way back into the book—not as readerly admiration, but as an autopsy of empathy gone wrong.

A marathon of misery

Hanya Yanagihara has said she wanted to write about friendship and devotion pushed to extremes. She chose gay male characters, she explained, because it freed her from the expectations of straight fiction—no marriages, no children, no conventional resolutions. It’s a strange kind of liberation, to use queerness as narrative freedom while erasing its reality. What she created instead was a closed system of suffering.

At the center stands Jude St. Francis, a man marked by every cruelty imaginable: childhood abuse, sexual assault, self-harm, addiction, paralysis, suicide. The prose is controlled, the pacing deliberate, the intent—empathy, perhaps—sincere. But after hundreds of pages, the horror ceases to illuminate and begins to accumulate. Each new trauma arrives not as revelation but as escalation.

Critics adored it. The New Yorker called it “subversively brilliant.” The Washington Post found it “devastating.” Even readers who hated it couldn’t look away. For many, the sheer intensity of pain felt profound. For others—especially queer men—it felt abstract, as though someone had imagined our anguish in perfect detail but missed our lives entirely.

Real experience is rarely this operatic. There are contradictions, humor, long quiet stretches between the moments that hurt. Without those textures, suffering becomes a special effect.

When fiction masquerades as testimony

Yanagihara never claimed autobiography. She called her novel a “fairy tale for adults,” a study in friendship and devotion, a “mythic” rendering of love. The problem isn’t that she wrote outside her experience—writers do that constantly—but that the culture received her invention as representation.

When A Little Life arrived, reviews described it as a work of radical empathy. Readers spoke of being “devastated” and “changed.” That language belongs to witness literature, to stories told from the inside. Yet this one came from the outside, and few seemed to notice.

Imagine a white novelist writing an eight-hundred-page saga of Black pain, then explaining that race was “incidental.” The backlash would be instant. But a woman writing about gay men? That distance was reframed as sensitivity.

Empathy from an outsider can look generous to the audience it comforts and false to the one it represents.

The James Frey comparison

The difference between fabrication that enrages us and fabrication that earns prizes isn’t honesty; it’s permission.

When James Frey published A Million Little Pieces in 2003, he called it a memoir of addiction and recovery. It sold millions until journalists discovered that large parts were invented. Oprah Winfrey, who had championed the book, publicly confronted him. Frey was shamed for bending truth in a genre that requires it.

Yanagihara, on the other hand, fabricated everything and was celebrated for it. She built a world of invented queer trauma, sold as empathy, and collected awards.

If Frey was punished for pretending his fiction was real, Yanagihara was rewarded for making her fiction feel real enough. That’s not ethics; that’s appetite.

Who gets to tell whose story

Over the past decade, a number of bestselling novels about gay men have come from straight women. They’re often graceful and compassionate, but the pattern is revealing: queer men remain the subjects of art, not its authors.

No one’s arguing that only insiders can write across difference, but power matters. When outsiders dominate the telling, empathy becomes replacement. Editors still believe a mainstream readership prefers “sensitive” gay stories filtered through a female author. That’s not inclusivity; it’s marketing.

Representation isn’t improved by displacement.

Authenticity versus comfort

The success of A Little Life shows how eager we are for safe empathy. The novel allows readers to feel compassionate without facing the mess of real queer lives—funny, ordinary, contradictory. Authenticity has always been slippery in art, but declaring identity “incidental” erases the world that shaped it. Maybe it takes a certain kind of privilege to believe identity can ever be incidental—and I say that as someone who’s benefited from that illusion.

That’s the ache behind the praise: a sense that the book gave audiences an emotional workout but taught them nothing about the people it seemed to portray.

The Stephen Fry mirror

Consider the contrast. When Stephen Fry spoke openly about his depression, addiction, and sexuality, he was called self-indulgent. When he wrote about those same experiences in Moab Is My Washpot and later memoirs, critics accused him of oversharing. He told the truth of a gay man’s life and was chastised for honesty.

Yanagihara imagined that life from afar and was praised for her empathy.

That’s the gap between comfort and truth—and it says everything about where we still stand.

“If James Frey was punished for pretending his fiction was real, Hanya Yanagihara was rewarded for convincing readers her fiction was real enough.”

Author’’s note: The Peter Hujar image on the original cover of A Little Life features an unidentified subject, not David Wojnarowicz as sometimes reported. The first audiobook was narrated by Oliver Wyman; a new version recorded by Matt Bomer was released in 2025.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This post may contain affiliate links, and I may earn a commission if you purchase through them at no additional cost to you.

Further Reading

If you like this series and are curious about books that have inspired me, I’ve curated a collection on Bookshop.org. Buying through that link supports independent bookstores—and it helps sustain this project.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

🧵 Join me on Threads: Caleb_Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

I vaguely remember reading this book. It was really well written but even then I thought it felt too much like "trauma porn". Personally, I find repeated sexual abuse in fiction to be quite off putting.

I don't really mind so much that Yanigihara is a woman. The whole point of fiction is that writers imagine the lives of people who are different from themselves. But the book was so unrelentingly tragic. In that way, it fed into stereotypes that queer stories are inevitably tragic.

Wow. Lots of comments below by people who haven't read it. Caleb, I respect you, but I disagree with your premise that a straight (or straightish or whatever) Asian woman can't write about gay men. Note that one of the main characters, one of the four, doesn't identify as being gay. He just loves one of the other men, deeply.

It's fiction. Fiction is fiction. We get to make things up, to imagine. I write about straight people all the time. I'm gay. Does that make my POV about straight people invalid? I've spent a lifetime observing them.

You said in your opening paragraph that after you finished the audiobook and you found it it wasn't based on anything, that it was made up--then you stopped feeling "reverence"--which is how you described feeling before you knew that factoid. That's confusing to me. Not all fiction needs to be drawn solely, or even partially, on the authors racial, gender, sexual identification, as it seems like you're suggesting. She's telling a story. The story has characters. Add plot. But the germ of fiction is in the imagination.

I remember being in the audience at a screening of The Kids Are Alright by queer filmmaker Lisa Cholodenko. In the Q&A someone took issue with the fact that one of the lesbian characters slept with a man. They challenged the *politics* of that choice. Cholodenko said (paraphrasing), "Hey I just set out to tell a story about these particular character. It's not my job as a filmmaker to advance any particular point of view or agenda. I'm just telling a story."

Maybe we can agree to disagree. I found the book profoundly moving, and however she came across these characters--maybe by direct observation of people she knew, maybe composite, maybe in a fever dream, or maybe just wholly fabricated; it doesn't matter to me.