Robert Redford’s Gatsby, and Why It’s Still the One

Robert Redford gave us the Gatsby we wanted to be—and the Gatsby Fitzgerald wrote.

Robert Redford died this week at 89, and with him goes not just one of Hollywood’s great actors but a whole era of American film. He wasn’t simply a leading man; he was a director, a producer, an activist, the founder of Sundance. He shaped American cinema both in front of and behind the camera. But for me, the role that lingers is his Jay Gatsby in the 1974 adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, The Great Gatsby.

The film itself has been picked apart for decades, dismissed by some as too pretty, too languid, too much of a coffee-table-book adaptation. But that judgment misses the point, because Fitzgerald’s story is about beauty that can’t last, a dream that slips through your fingers as soon as you reach for it. Redford’s performance—and the film around him—captured that more faithfully than any other attempt.

The Golden Boy as Tragic Dreamer

In the early 1970s, Redford was America’s golden boy: blond, athletic, impossibly handsome. He had already made Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Candidate. He was more than a star; he was a symbol of American promise.

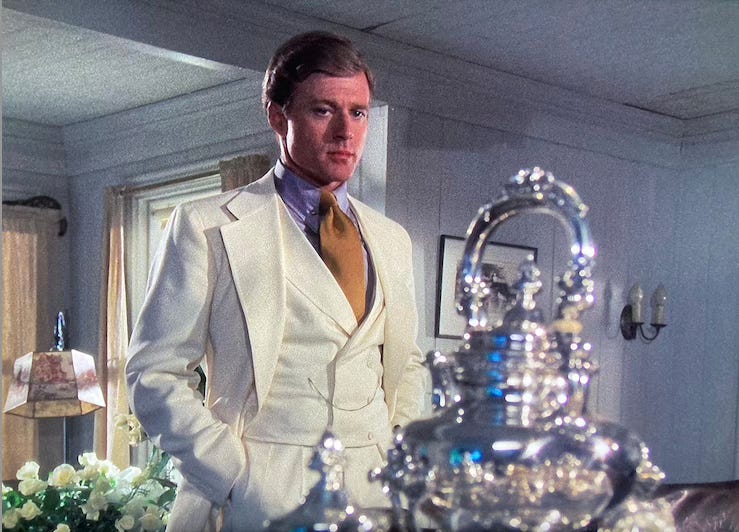

And that’s why his Gatsby works. He carries himself with poise and restraint, the mask of a man who appears to have everything while hiding a hollow center. He isn’t manic, he isn’t deranged, he isn’t the fevered DiCaprio version shouting “old sport” across a glittering circus. He’s still, quiet, his desperation glimpsed only in the set of his jaw, the catch in his voice, the look in his eyes as they fix on a light across the bay.

Redford makes Gatsby’s delusion noble. You believe in him not because he dazzles but because he aches. He’s the Gatsby you want to be—the one who has built an entire persona from scratch, willing himself into existence, not for wealth itself but for a dream.

Aspiration vs. Seduction

This is where the comparison with Leonardo DiCaprio becomes useful. Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation gave us Gatsby as fever dream—fireworks, Jay-Z, champagne spilling over. DiCaprio was magnetic, but his Gatsby wasn’t someone you identified with. He was someone you wanted to be consumed by. His was a seduction, not an aspiration.

That’s the split between the two versions. Redford’s Gatsby represents aspiration—an ideal of poise and control, a man who keeps his tux pressed and his mask firmly in place until it cracks. DiCaprio’s Gatsby embodies seduction—chaos in a white suit, passion as spectacle, a man you want to fall into even as you know he’ll burn you down.

Both are present in Fitzgerald’s novel. But the quieter tragedy, the sense that the dream collapses not with fireworks but with silence, belongs to Redford.

A Film That Trusted Beauty

The 1974 film, directed by Jack Clayton with a script by Francis Ford Coppola, leaned into beauty as metaphor. Critics complained that it was drenched in chiffon and chandeliers, every frame polished to a Vogue-like sheen. But what else should Gatsby’s world look like? Fitzgerald described a universe shimmering with impossible perfection, so bright you almost go blind. To accuse the film of being too pretty is to miss the point: the glitter is what makes the fall hurt.

Daisy’s Voice, Full of Money

Mia Farrow’s Daisy was another lightning rod for criticism. She was called shrill, shallow, insubstantial. And she is. But Daisy isn’t meant to be a goddess. As Fitzgerald wrote, “Her voice was full of money.” She is meant to be the embodiment of Gatsby’s tragic blindness—a fragile, infuriating figure who can never live up to the dream projected onto her. Farrow played that well, making Daisy at once believable and unbearable. You understand why Gatsby can’t let her go, and why everyone else can see the futility.

In Keeping with Fitzgerald

What the 1974 film captured, more than any other adaptation, was Fitzgerald’s tone. The novel is not about parties. It is about what the parties conceal. It is about longing and silence, about beauty that crumbles, about people chasing what they can never hold. Fitzgerald ended with the famous line about “boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Redford’s film understood that mood. It didn’t shout at us. It trusted us to feel the ache of a dream slipping away.

A 1970s Gatsby

The timing of the film mattered too. In 1974, America was in disarray. Watergate was unraveling the presidency. Vietnam had drained idealism. The country felt exhausted, uncertain of its own myths.

To revisit the Jazz Age then was to revisit another moment of glitter over rot. The nostalgia for the 1920s that ran through the film was really nostalgia for something America felt it had already lost: innocence, possibility, the promise of a better tomorrow. Redford’s Gatsby stood at the intersection of those feelings. He was both fantasy and critique, promise and disillusionment.

Beyond Gatsby

Of course, Gatsby was just one role in a career that stretched across decades. In All the President’s Men, Redford turned investigative journalism into a cinematic thriller, giving Bob Woodward the kind of cool intensity reporters only dream of. In Three Days of the Condor, he embodied Cold War paranoia with that same taut restraint. And when he directed Ordinary People, he proved he could elicit raw, shattering performances from others.

He was more than a star. He was a cultural force, using his fame to elevate independent voices through Sundance. Without Redford, countless filmmakers—from Quentin Tarantino to Ryan Coogler—might never have found a platform.

But Gatsby remains singular, because it was the role where Redford’s public image and Fitzgerald’s character fused into one. The golden boy chasing an impossible dream. The man who seemed to embody American promise revealing the cracks beneath.

A Personal Memory

Growing up, my mother had a small set of Fitzgerald’s books on a shelf. They were bound in black cloth with silver lettering—a uniform edition published by Scribner in the late 1960s and early 1970s, part of a push to re-establish Fitzgerald in the American canon. Even The Last Tycoon—the novel he never finished—was there. Just seeing the titles lined up made me want to read them all.

I started with The Great Gatsby in middle school and worked through the rest, with This Side of Paradise becoming my favorite. I’ve read them all since then, with Tender Is the Night standing out as his most ambitious and heartbreaking.

For me, Gatsby is Fitzgerald’s greatest character, and Redford embodied him perfectly. I think as humans—but particularly as gay men—we understand the longing for something we can’t have, or at least something that isn’t good for us. Gatsby’s devotion to Daisy, absurd as it seems, feels familiar: chasing a dream because it sustains you, even when everyone else knows it will undo you.

The Shirts

And even at that age, watching the 1974 film for the first time, I understood it in my bones. When Redford’s Gatsby pulled stacks of shirts out of his wardrobe and let them tumble onto Daisy—linen, silk, sheer cloth in every color—I wanted to roll in them too. That scene, so extravagant and so silly, became the purest image of desire I had ever seen. Not sex exactly, but something adjacent: the hunger to be surrounded by beauty, to be wrapped in a dream, to lose yourself in the texture of a life just out of reach.

Forever Believing

Now, with Redford gone, that performance takes on an even deeper melancholy. He wasn’t just playing a man chasing a past he couldn’t reclaim; he becomes part of our own nostalgia. Watching him now is like watching the dream of a different Hollywood—an industry willing to be quiet, willing to trust beauty, willing to let melancholy do the work.

There will be more Gatsby adaptations, because Hollywood can’t help itself. But we don’t need them. Redford already gave us the version that matters. He gave us aspiration rather than seduction, tragedy rather than frenzy, beauty rather than noise. He gave us a Gatsby that felt faithful to Fitzgerald’s prose—restrained, melancholy, shimmering with a dream already slipping away.

And now, with his death, that dream feels all the more poignant. Because it isn’t just Jay Gatsby staring out at the green light anymore. It’s Robert Redford himself, forever young, forever tragic, forever believing.

Books & Films Mentioned

If you’d like to revisit Fitzgerald or Redford:

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Line & Verse for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

🧵 Join me on Threads: Caleb_Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed