Making Monsters: On Frankenstein, Desire, and the Stories That Make Us

A teacher, a monster, and the first time art looked back at me.

I was in high school when I first met the Romantic Period. It was an advanced English Literature Class with no more than 20 students. Our teacher was a legend in her own right and certainly the most decorated of the school’s faculty. She had a terminal degree from a fancy “northern” school and had lost count of how many times she had been named the district’s “Teacher of the Year.” I say all this to preface, she was the type of teacher that administration was afraid of, they left her to run the English Department and to teach as she saw fit.

I wish I could remember more, but this kicked off a unit that introduced the romantic poets Shelley (Percy), Byron, and Keats then led into the gothic with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Two years prior, she’d already scandalized the faculty once by showing us Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968). The movie arrived the way all “educational media” did back then: a 200-pound Sony Trinitron lashed to a metal cart with a ratcheting strap—supposedly for safety, though it always looked ready to crush whoever dared wheel it down the hall. She rolled it in like a sacred relic, the strap creaking, the fluorescent lights humming. When Olivia Hussey and her ample, uncovered bosom appeared, all four-ten of her tried to stand in front of the screen, a heroic act of futility that taught us more about beauty and restraint than the play ever could. I like to think that there is a whole generation of boys who remember Olivia Hussey as the first time they saw a naked woman - at least that was my thought when she passed away in late 2024.

So, when that familiar television returned for a screening of Haunted Summer (1988), none of us expected innocence. “Context,” she said, cueing the obscure, candlelit film about the Shelleys and Byron telling ghost stories by Lake Geneva. The film starred Philip Anglim as Byron and Eric Stoltz as Shelley, alongside a pre-Bill & Ted Alex Winter and a young Laura Dern. Characters wandered half-dressed and high, arguing and aching for things they couldn’t name. Here was Frankenstein’s origin story, presented as a beautiful, fevered breakdown.

Most classmates were mortified; I was hypnotized—especially noting Stoltz’s early full-frontal cameo. It seemed fitting that the same teacher—daughter of a high-ranking Episcopal church official—was responsible for showing me both my first cinematic breasts and my first cinematic full-frontal. Art, morality, and education all colliding in one English department. Our teacher never explicitly discussed sexuality or queerness, but she didn’t have to. Frankenstein spoke clearly enough on its own: men creating life without women, a being stitched together from the discarded and forbidden, punished not for crimes but visibility itself. If that’s not a queer metaphor, language has failed us. She let us sit with that discomfort, giving space for lessons we weren’t yet ready to articulate.

When Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein came out in 1994, our class organized an unofficial viewing at the mall multiplex. It was mid-90s gothic excess: De Niro’s stitched body trembling beneath candlelight, Branagh’s beautiful yet flawed Victor, Helena Bonham Carter embodying grief and loss. Walking out afterward, I was unsettled—not frightened, but awakened. The film exposed something fundamental about creativity itself: the fear of your private obsessions coming to life and staring back at you. Years later, I recognized this feeling as intrinsic to queerness—the thrill and fear of visibility.

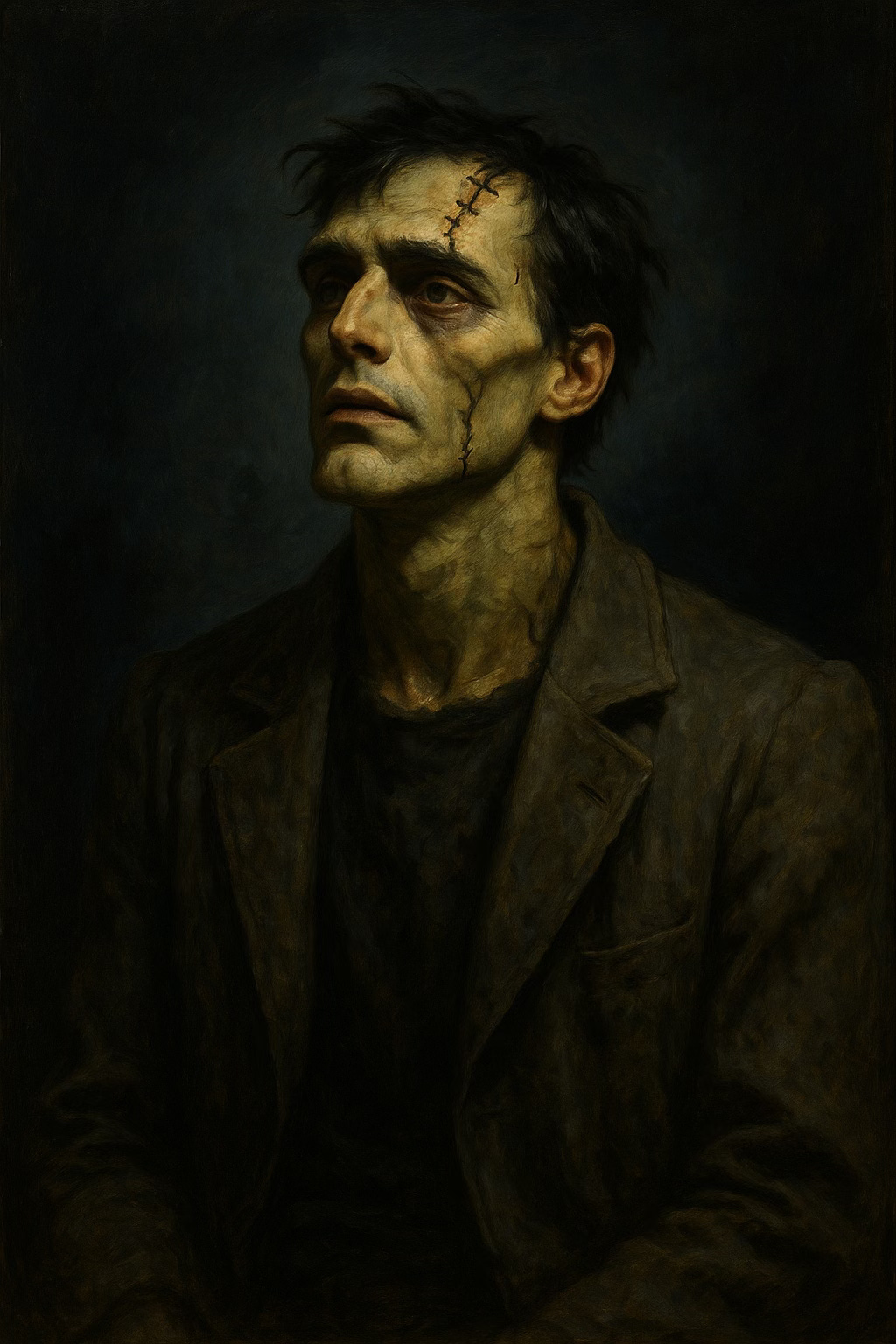

Decades later, there’s a new Frankenstein streaming this week—Jacob Elordi playing the creature, Netflix money and Guillermo del Toro directing. Before the trailer even dropped, I could tell the marketing would be obsessed with Elordi: all height and haunted eyes, the internet’s current patron saint of beautiful alienation.

If the adaptation stays faithful, it will probably do what every Frankenstein retelling does—pretend to be about science while quietly dissecting intimacy. But Elordi as the creature changes the chemistry. Suddenly the “monster” isn’t grotesque; he’s sublime. He’s every impossibly perfect man punished for being too much of what he is.

After Seeing It

I finally watched the film, and it’s almost disorienting to say this, but it might be the best adaptation of Frankenstein I’ve ever seen. Del Toro actually read the book — you can feel it in every frame. The tenderness is intact. The creature’s longing is intact. Even the awful, humiliating ache of wanting to be loved is intact.

Most adaptations treat the monster like a special effect. This one treats him like a tragedy in progress. You don’t brace for him to lunge; you brace for him to speak, because you already know his voice is going to ruin you a little.

And Jacob Elordi — irritatingly, inevitably — is perfect. He makes the creature’s beauty uncomfortable, which is exactly what Shelley intended. You’re not supposed to know whether to pity him or fear the moment he realizes what he is.

What the film gets right, more than anything, is Victor. Not as a mad scientist or a misunderstood genius, but as a young man who never bothered to think past creation. He wasn’t cruel in the mustache-twirling way; he was cruel in the careless way. The worst kind. He never imagined what his creature would need, only what he himself could achieve. It’s the textbook arrogance of a boy who wants the glory of making life but none of the responsibility of tending it.

For once, a filmmaker understood that the real horror isn’t the monster — it’s the parent who never considered what happens after the spark.It’s the same story all over again: creation, rejection, self-knowledge. Only this time, the gaze lingers.

Romanticism has always been coded queer; it just didn’t have the vocabulary. Byron’s swaggering vanity, Percy Shelley’s utopian fluidity, even Keats dying young and tender—it’s all a map of desire turned inward. When the world said “unnatural,” they said “sublime.”

The Gothic grew out of that same soil. These were people obsessed with bodies, boundaries, and what happens when either one dissolves. Frankenstein, Dracula, Dorian Gray—each a different mask for the same fear: that passion will expose you. That wanting is dangerous.

Mary Shelley wasn’t writing a horror story. She was writing the autobiography of repression itself. The creature’s real tragedy is not that he’s unloved but that he knows he’s unlovable. He learns language, empathy, music—and it condemns him. Enlightenment as damnation.

That’s the queer condition in shorthand.

Revisiting Haunted Summer recently (now streaming on Amazon Prime), I found it almost documentary-like—beautiful, self-aware, mythic. Byron flirted with his reflection; Percy championed freedom while neglecting those around him. Mary, quietly absorbing chaos, transformed pain into art. Though largely ignored upon release, the film captures queer Romanticism’s creative voltage perfectly.

Frankenstein adaptations hinge on one moment: the creature seeing his reflection. Netflix will inevitably feature this moment. It won’t highlight horror, but self-awareness: the creature understanding he’s both masterpiece and mistake. Every artist, queer kid, and human being encounters this profound realization—creating something that accurately reflects yourself and learning to survive its implications.

Perhaps this enduring relevance keeps calling me back. Frankenstein isn’t about monsters; it’s about authorship. Years spent assembling fragments—career, identity, queerness, ambition—revealed themselves as pieces of the same experiment. Victor’s animating spark was my own: the desire for visibility and the strength to survive it.

Netflix might decorate Frankenstein with special effects and cinematic polish, but the heart remains Mary’s: loving something enough to bring it to life and spending eternity trying to understand it. The new adaptation’s true intrigue won’t be the creature’s appearance, but the gaze—who sees whom, and why.

Maybe this time the creature will achieve the tenderness Shelley desired. Perhaps he’ll be allowed beauty without apology. After centuries of punishing the “unnatural,” perhaps we’ll witness genuine compassion.

In retrospect, my high school English teacher, covered in chalk dust, persistently teaching “the sublime,” understood her lessons might only resonate decades later. She was right. She taught us empathy—to witness the creature without flinching. As my own life reformed into something authentic, her lessons surfaced: you cannot destroy what you’ve created, only love it more deeply.

This, then, is Frankenstein’s hidden mercy: the creature isn’t evil—he’s evidence.

Epilogue: On Making and Being Made

We all create monsters—art, ambitions, relationships, careers—and spend our lives learning to claim them. Frankenstein endures because it’s fundamentally about responsibility—to what we create and what it reveals about us.

Looking back at that classroom, the flicker of Haunted Summer, and De Niro’s stitched portrayal, I see myself learning what stories offer—not explanations of the world, but the tools to survive it.

Perhaps this is why I chase this narrative. Between Mary’s storms, Byron’s vanity, and the creature’s reflection lies a simple truth: every act of creation is the same ongoing experiment—a human attempting to give life to something real.

And hoping, desperately, it never turns against them.

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you.

Further Reading

If you like this series and are curious about books that have inspired me, I’ve curated a collection on Bookshop.org. Buying through that link supports independent bookstores—and it helps sustain this project.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

🦋 Bluesky: @thecalebreed.bsky.social

I'd forgotten about Juliet's breasts. I seem to recall Romeo's butt, though. Haha

All those classics, points taken and paths made, storylines not the mainstream understanding but something more.