The ride north felt shorter, though Ethan kept the windows cracked the same way.

Habit, maybe. Or superstition. The same Beck CD skipped in the same places when the Jeep hit certain seams in the road; he could almost feel them coming before the tires did. Somewhere around Rocky Mount the last trace of salt left the air. By the time he crossed into Virginia, the sky had flattened into that particular gray that always felt like it belonged to Westmore.

He topped the hill before the exit and saw the bell tower first, cutting the horizon. The campus spread out beneath it in familiar lines: quad, chapel, a smudge of Fraternity Row through the trees. It should have felt like coming back. Instead, it felt like walking into the last scene of a play he already knew the ending to.

Inside the gates, the roads were dusted yellow. Pollen clung to windshields and brick. Campus waited behind a veil of early light and spring grit, red buildings shining wet from last night’s rain.

Magnolia petals stuck to the sidewalks like damp paper. Trash cans overflowed with Styrofoam cups, their sides collapsing in on themselves. A banner between two lampposts drooped in the still air: GOODBYE SENIORS, the middle letters warped by water, the exclamation point half torn.

Fraternity Row looked professionally laundered. White columns scrubbed, hedges clipped with mean precision, front lawns picked clean of beer cans and cigarette butts. Banners for Senior Week had already gone up—giant, overly cheerful things with dates and slogans that tried too hard. The same Greek letters that once felt like gatekeepers now looked like decorations you could take down with a ladder and a free afternoon.

His eyes went to the end of the Row automatically, to the spot where Eli’s truck was always crooked in the gravel, tailgate scarred, old lacrosse sticker peeling on the bumper. The space was empty.

The silence felt earned.

He parked behind McClintock and sat there a moment with his hand on the key, listening to the engine tick itself down. Somewhere across the quad, a staticky version of “Closing Time” leaked from somebody’s radio. He killed the ignition and let the quiet expand around him.

Inside, the dorm smelled like lemon cleaner and hot pipes. Open doors exposed stripped beds and bare bulletin boards. Most were not staying for graduation. Fresh tape squares waited on some doors where new names would go in August; others had old name tags curling at the corners, pulled away and stuck back too many times.

Mark’s bed was already stripped, mattress bare except for a single folded towel in the middle. His side of the room looked wrong without the mess—no pile of laundry at the foot of the bed, no stack of empty Coke cans, no Rush shirts on the chair.

Ethan set his duffel on his own bed. The springs complained the familiar way. He unpacked slowly, not so much moving in as setting things down—books on the desk, cigarettes in the top drawer, the cheap halogen lamp with its crooked shade back in its usual place.

He stopped once, hand resting on the edge of Mark’s mattress. The absence felt louder than any argument would have.

He showered, put on a clean shirt that still smelled faintly like his mother’s detergent, and walked across the quad to Broadmoor.

Dr. Carroll’s office seemed smaller without the fortress of lab reports on every surface. There was space on the shelves now, gaps where journals had been returned to their proper volume order. Light slipped between the blinds in sharp white bars, striping her desk, her hands, the manila folder with his name on it.

She signed his grade sheet without ceremony. “You came through it intact,” she said.

“Barely.”

“Barely counts.” She uncapped and recapped her pen like a period. “The hard part isn’t leaving. It’s not becoming what they told you to be once you go.”

He didn’t answer right away. She looked up, and the air shifted. She had the kind of gaze that made excuses die before they reached your mouth.

“You know what you are now, don’t you?” she asked.

He nodded. The word itself stayed in his chest, but the nod felt like saying it out loud.

“Good,” she said. “Don’t apologize for it. Not here. Not when you leave. Especially not when you leave. It’ll save you years.”

It landed with more weight than any exam grade.

Outside, magnolia blossoms drooped under their own size, edges already browning. He stood under one, tucked between the branches and the building’s shadow, and tried to picture his life beyond this place. The curve of it was still more feeling than outline, but for the first time the blank space didn’t scare him.

He wanted that blank space to stay his.

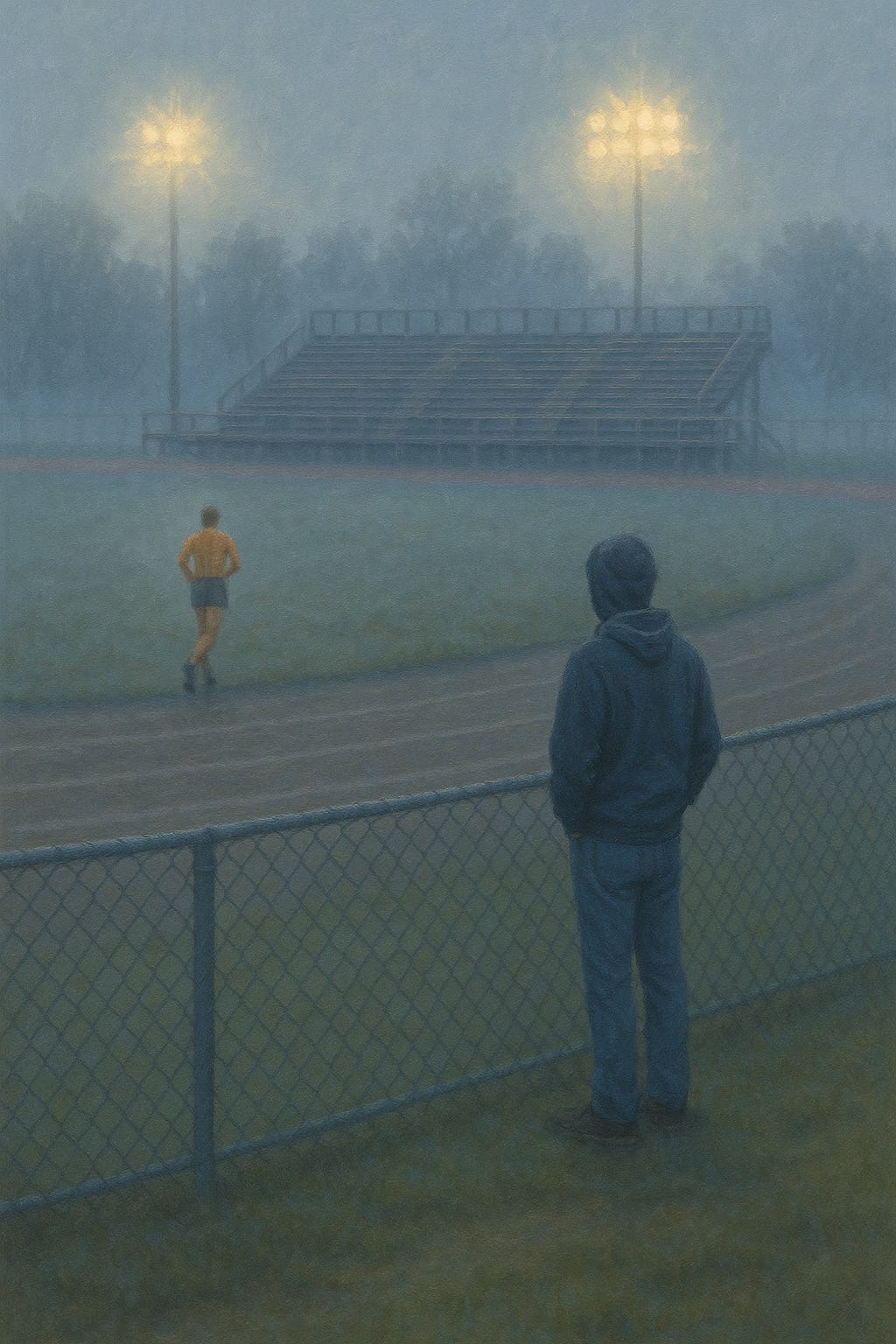

The next morning Tyler ran the perimeter road before sunrise.

Mist clung low to the track, wrapping the far turn in a gauzy blur that burned off slowly under the floodlights. His breath came out in small, white ghosts. Running early made the day feel possible. It was the only time nothing and no one was asking anything of him.

Halfway through his second lap he noticed a figure near the bleachers, hands in his pockets, shoulders hunched against nothing in particular. Ethan. He wasn’t watching the runners. He was staring at the field—the empty rectangle where games had been played, parties thrown, tents set up, and where, in a week, rows of chairs would mark off a final ritual.

Tyler slowed coming off the turn. The gravel under the old cinder layer popped beneath his shoes. He could have pretended he hadn’t seen him. It would have been easy enough: head down, pick up pace, let the fog do the work.

Ethan turned as if he’d felt something change. Their eyes met over the low chain-link fence.

Tyler lifted his chin, the smallest acknowledgment.

Ethan nodded back. No wave, no call over the hum of the lights.

It was nothing. It was everything.

Tyler lengthened his stride again. He didn’t know exactly what had broken between Eli and Ethan over Spring Break, but he knew the shape of the cracks now: in the way Ethan held his shoulders, in the way Mark’s voice changed when he said his brother’s name, in the fact that Ethan was out here at dawn, staring at a field instead of sleeping.

Whatever came next would be quieter, less fueled by denial.

Quiet, he could work with.

Senior Week didn’t feel particularly senior.

The college had printed schedules with logos and titles—Senior Toast, Honors Convocation, President’s Reception—but it all blended into one long, mismatched reel. One day bled into the next in a way that felt more like August than May—everyone slightly off balance, looking for where they belonged without admitting that’s what they were doing.

By afternoon there were cookouts: paper plates, borrowed grills, yellow beer in plastic cups. By evening the houses filled; by night the Annex took whoever was still vertical.

Ethan found himself at the house most nights, not because he wanted to celebrate anything, but because it felt worse to sit alone in a half-empty dorm.

Jason moved through it all with a kind of tired ease, shaking hands with alumni, letting mothers hug him, taking photos with freshmen he barely knew. Clay barked at nobody in particular about cooler placement and trash bags, trying to make his clipboard matter a little longer before he finally graduated and had to pass it on. Connor and Teddy turned everything into a bit, laughing too loud, trying to stretch their roles as comic relief into some kind of armor.

Eli drifted like weather: appearing on the porch with a cigarette, vanishing into a circle of alumni, reappearing later at the keg. If you didn’t know anything else, he looked fine. Better than fine. Relaxed. He’d landed a job in New York. He slipped talk of it into conversations without sounding like he was bragging. He made Catherine laugh at the right times.

The only time Ethan saw the mask slip was at the Annex.

It was late; the party had bleached itself out. Most of the bodies had moved back toward campus or deeper into the yard, but Ethan had stayed behind.

Eli stood at the kitchen sink, hands braced on the edges, head tipped down. The harsh overhead light picked out the lines at the corners of his mouth that weren’t there in August.

For a moment, he was unguarded. Not tragic, not dramatic. Just… tired. The kind of tired that comes from holding something shut for too long.

Ethan stayed in the doorway, watching. He didn’t say anything.

Eli turned on the tap, splashed water on his face, rolled his shoulders like someone shaking off a hit. When he straightened and turned, his expression had reset: mouth curved, eyes bright, the familiar version of himself back in place.

“Place still standing?” he said, as if nothing inside him had shifted at all.

“Barely,” Ethan answered.

“Barely counts,” Eli said, without knowing he was quoting someone else.

Mark came back to McClintock on Wednesday.

Ethan heard him before he saw him: the stumble of his boots down the hall, the familiar cadence of his laugh, the door creaking open like every other time that year. For a second, motion and memory blended and it felt like September again.

Then Mark stepped in, and it wasn’t September.

He looked the same on the surface—sun-bleached hair, worn ball cap, T-shirt half tucked in, keys hooked around two fingers. But the easy looseness was gone around the edges. His eyes flicked automatically to Ethan’s side of the room, then away, like he didn’t trust himself to look for too long.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey.”

He tossed his keys onto the desk, missed, let them bounce off the floor and lie there. “Parents are staying at that crappy motel off the highway,” he said. “The one with the ‘Color TV’ sign like that’s still a selling point.”

Ethan huffed a small laugh. “Classy.”

“Yeah.” Mark dropped onto his bed, the bare mattress thunking against the frame. “They brought my grandmother. She asked if I had any nice girls coming to graduation.”

“What’d you tell her?”

“That I go to Westmore,” Mark said. “Nice girls are shipped in on weekends only.”

Ethan smiled despite himself. They sat in the thin truce of shared jokes for a moment.

Mark leaned over, pulled a Coke-can from the thrash, and set it on the windowsill like it belonged there. He lit a cigarette, exhaled toward the screen.

“You know he told me,” he said finally. “Down at the coast.”

The air changed.

Ethan stared at the pattern in the floor tile between their beds. “Yeah,” he said. “He said he might.”

“He didn’t ‘might.’ He did.” Mark tapped ash into the can. “Sat there on the deck like we were swapping fishing stories.”

“I didn’t ask him to.”

“I know.” Mark’s tone wasn’t accusing on that point, and somehow that made it worse. “He’s still my brother, you know. That doesn’t go away because he decided to… expand his resume.”

Ethan let out a breath. “I never wanted to take anything from you.”

“Intent’s not the problem,” Mark said. He turned his head finally, looking at him full on. There was anger there, sure, but underneath it something more complicated: hurt, confusion, a kind of grief. “My whole life, he was the guy I was supposed to be someday. The map. And now I’m supposed to make sense of the fact that the map left out an entire other continent.”

He laughed once, without humor. “And you’re standing there holding the passport.”

“It wasn’t about you,” Ethan said, quiet, because anything louder would have felt like an argument.

“You think I don’t know that?” Mark snapped, then checked himself. “I know it wasn’t about me. That’s half of why I’m pissed. The other half is—” He broke off, jaw tensing. “I don’t even know what the other half is.”

They sat in it.

“He said it was a mistake,” Mark added after a beat. “You buy that?”

Ethan thought of Eli’s hand at the base of his neck, of the Underground farmhouse, of the way Eli had looked afterward, wrecked in a way that had nothing to do with what they’d done and everything to do with what he couldn’t admit. He thought of Tyler’s quiet steadiness on the dock, the weight in Jason’s voice whenever he said be careful what you let this place take from you.

“No,” Ethan said. “I think he was scared. I think calling it a mistake was easier.”

Mark stared at him for a long moment. “You in love with him?”

Ethan swallowed. “I was.”

“And now?”

“Now,” Ethan said, “I’m trying to stop wanting to fix a thing that doesn’t want to be fixed.”

Mark looked away first. “He loved you,” he said, almost under his breath. “He doesn’t have the language for it, but he did. Does. That’s part of the problem.”

Ethan pushed his hands into his pockets so Mark wouldn’t see them shake. “It’s not your job to carry that for him,” he said. “Or for me.”

“Doesn’t matter,” Mark muttered. “I’m the little brother. That’s the whole gig.”

He ground the cigarette out in the can, the metal pinging. “I don’t hate you,” he said. “I want to. Would be simpler. But I don’t.”

Ethan nodded. “I know.”

“I just don’t know what we are now,” Mark went on. “You and me. Me and him. It’s not what it was in August. That’s gone.”

“Yeah,” Ethan said. “It is.”

They sat with that, each word settling like dust on furniture that wouldn’t be there next week.

“I’m not ready to be okay about any of this,” Mark said finally. “So don’t try to fix it for me. Don’t… use that quiet, reasonable voice on me. Not now.”

“I’m not,” Ethan said. “I don’t know how to fix it either.”

“Good,” Mark said, but his voice had lost some of its hard edge. He pushed off the bed. “I’m heading back to the motel. Mom wants one last ‘family dinner’ where Dad complains about tuition and Nana compliments the biscuits until the server takes it as a personal attack.”

He moved toward the door, then paused with his hand on the knob. “I don’t think this is it for us,” he said without turning. “You and me. I just… need some distance before I figure out how to look at you without seeing him.”

Ethan’s throat tightened. “Take what you need.”

Mark nodded once, almost imperceptibly, and left.

The room felt wrong after that—too big on one side and too small on the other.

It was late when the knock came.

The houses on the Row had hit that point in the night where noise becomes a kind of weather: laughter, music, some guy on the porch yelling the same story for the third time. It seeped across the quad and through the thin dorm windows as a single muffled roar.

Ethan lay on his back, staring at the ceiling. He hadn’t turned the overhead light on. The lamplight carved the room into soft wedges of gold and shadow, highlighting boxes, an open suitcase, the bare geometry of Mark’s empty bed.

The knock was soft, almost an afterthought.

“Yeah?” he said.

“It’s me.” Tyler’s voice through the door.

“Come in.”

Tyler slipped inside and closed the door behind him with care, as if noise itself were a thing they should respect. He looked tired in the particular way that came from being the one everyone leaned on all week.

“You okay?” he asked.

“Define okay.”

“That’s a no, then.”

Tyler moved to the chair at Mark’s desk but didn’t sit. He turned it around and dropped into it backward, arms folded across the back, chin resting on his forearms. It was a posture Ethan had seen him use at the Annex, in the basement, watching the room. Only now the room was just him.

“You talked to Mark,” Tyler said.

“Yeah.”

“How bad?”

Ethan let out a breath that felt like it had been sitting there all day. “He said he doesn’t hate me. He just doesn’t know how to look at me right now.”

Tyler nodded. “That sounds about right.”

“He kept talking about maps,” Ethan said. “How Eli was his map, his model. And now he feels like there’s this whole other thing he didn’t know about. And I’m standing there like proof.”

“Proof isn’t the enemy,” Tyler said. “It’s just uncomfortable.”

“He asked if I was in love with Eli.”

“What’d you say?”

“That I was,” Ethan said. “Past tense.”

“And now?” Tyler asked.

“Now I feel stupid,” Ethan said. “And relieved. And like I’ve somehow blown up two people’s lives by existing.”

Tyler studied him for a moment. “Do you really think you did that? Blew-up-two-lives single-handed?”

Ethan stared at the scuffed place on the floor where Mark’s desk chair had always rocked. “Feels like it.”

“Feeling,” Tyler said, “is not the same as fact.”

“You and Dr. Carroll ought to start a club,” Ethan said.

“We’d make you president,” Tyler answered.

The corner of Ethan’s mouth twitched. It didn’t quite become a smile, but it was proof he still knew how.

“I thought about transferring,” he said, after a moment. “Just… disappearing. Starting somewhere I’m not already a story.”

Tyler didn’t flinch. “Have you ever run from anything in your life before this?”

“I don’t know. Maybe I should have.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

Ethan rolled onto his side, facing him. “No. I haven’t.”

“So why start now,” Tyler said, “right when you’ve finally stopped lying to yourself?”

The words sank in.

“I don’t know how to be here like this,” Ethan admitted. “With Mark knowing something. With Eli still… orbiting. With you and me being whatever we are. I don’t know how we fit.”

Tyler shifted from the chair to the edge of the bed, close enough that their knees touched. “We don’t have to figure out the whole map tonight,” he said. “Just the next turn.”

“What’s the next turn?”

“Question one,” Tyler said, ticking it off on his fingers. “Do you want to be done with Eli?”

“Yes.”

“Question two: do you want… this?” He gestured, not broadly, but with a small, open-palmed gesture between them. “Me. Us.”

Ethan’s chest felt tight, but not in the bad way. “Yeah. I do.”

“Then that’s the next turn,” Tyler said. “We keep going. Here. Next year. We do it on our terms.”

“Our terms,” Ethan repeated. “Which are what, exactly?”

“Honest, quiet, not suicidal,” Tyler said. “You don’t have to be out to the world. You don’t have to put a rainbow sticker on the Jeep. You just have to stop pretending with yourself. And with me.”

“I don’t want to hide,” Ethan said. The words surprised him by how easily they came.

Tyler’s breath left him in a slow exhale he might not have realized he’d been holding. “Okay,” he said. “Then we won’t. Not from each other.”

“What about everyone else?” Ethan asked.

“We let them catch up or not,” Tyler said. “That part’s on them.”

The room was quiet except for the radiator and the distant thump of someone’s stereo. Rain started up again, a light patter against the window.

“You’re the only part of this place that makes sense,” Ethan said, before he could overthink saying it.

Tyler blinked. Then, slowly, he smiled. “Good,” he said. “Then don’t let Eli’s mess or Mark’s shock push you out. They’re allowed to feel whatever they feel. You’re allowed to stay anyway.”

Ethan looked at him, really looked at him—at the shadows under his eyes from too many late nights, at the small scar near his hairline from some forgotten childhood collision, at the calm that didn’t feel like a pose.

“Can you…” Ethan started, then stopped. “Will you stay? Tonight?”

Tyler didn’t joke. Didn’t ask with his eyebrows if Ethan was sure. He just nodded.

“Yeah,” he said. “I’ll stay.”

He toed off his shoes and eased back onto the mattress. It was a narrow bed; they had to negotiate space with care. They lay side by side at first, both staring up at the faint cracks in the paint that made their own map.

After a few seconds, Ethan rolled onto his side, turning toward him. Tyler mirrored the movement. The gap between them shrank.

“Is this okay?” Tyler asked.

Instead of answering out loud, Ethan leaned in and kissed him.

It wasn’t a question; it wasn’t an apology. It was an answer to something that had been humming under his skin since that night on the porch during Hell Week, since the Underground farmhouse, since that quiet joint on the back steps.

Tyler’s hand came up, fingers resting lightly at the base of Ethan’s neck, thumb brushing the line of his jaw. He didn’t pull him closer; he just held him there, as if to say you’re allowed to stay.

The kiss stayed slow. No rush, no grab. When Ethan deepened it, Tyler followed his lead, not trying to steer.

At some point, Ethan’s hand found the hem of Tyler’s sweatshirt, the soft cotton rising under his fingers. Tyler sat up just enough to let him tug it over his head. The shirt landed somewhere on the floor, forgotten. Underneath, Tyler was warm, his skin smelling faintly of chlorine and soap and something that was just him.

Ethan’s own T-shirt joined it a moment later.

They lay back down, bare shoulders touching this time, the contact electric in a way that didn’t scare him. Tyler’s fingers traced a slow line from his shoulder down to his elbow, like he was memorizing the route.

“You sure?” Tyler murmured.

“Yeah,” Ethan said. “I’m sure.”

The world narrowed in a good way.

They kept it simple. Kissing, mostly. Hands exploring—hesitant at first, gaining confidence as they read each other’s breaths, the way they tensed and softened. Jeans stayed on longer than they needed to. When buttons eventually popped and zippers edged down, it happened without fanfare, like the natural next step in a conversation that had been going on all year.

At some point they ended up pressed closer, legs tangled, hips aligned. Ethan felt Tyler’s breath stutter against his mouth and pulled back enough to see his face, to make sure.

Tyler’s eyes were open, steady. “Still okay,” he said.

They moved together, uncoordinated for a second, then falling into a rhythm that felt less like something they were doing and more like something that was finally being allowed to happen. Heat built slowly, not like a match flaring but like coals catching.

Ethan’s world shrank to small things: the warmth of Tyler’s palm at his back, the press of their foreheads, the soft sound Tyler made when Ethan slid a hand along his side, the way their breaths caught at the same time and then refused to sync up again.

When it crested, it wasn’t loud. There were no declarations, no shouted names. Just a sharp inhale, a gasp, fingers clutching at shoulders, everything going white around the edges for a few seconds, then fading back in with the pulse of their breathing.

After, they lay sprawled on the narrow bed, half tangled, skin damp, hearts still drumming.

“For the record,” Tyler said quietly, once his lungs remembered what to do, “still not running?”

Ethan let out a breath that felt like it came from somewhere below his ribs. “No,” he said. “Not running.”

Tyler shifted onto his back, pulling Ethan with him until his head rested on Tyler’s chest. His skin was warm; his heartbeat was steady. Ethan could hear it under his ear, a metronome that finally matched something in him.

“You okay?” Tyler asked.

“Yeah,” Ethan said. The answer surprised him by how true it felt. “I am.”

“Good.” Tyler dropped a light, almost absent-minded kiss onto his hair. “Me too.”

The rain kept up its thin percussion at the window. Somewhere down the hall, a door closed, footsteps passed, water ran in a pipe. The world outside hadn’t changed. Inside the small rectangle of mattress and blanket, everything had.

They didn’t talk anymore. They didn’t need to.

Sleep crept in quietly. Ethan let it, his last conscious thought a simple one: that for the first time since stepping onto campus in August, he didn’t feel like he was performing being himself.

Morning came soft.

Light pressed around the edges of the blinds, washing the room in a gray that hadn’t decided yet what kind of day it would be. The rain had moved on. The air through the cracked window was cool and clean, carrying the faint smell of cut grass from somewhere down on the quad.

Ethan woke slowly, aware first of warmth, then of weight—Tyler’s arm draped across his stomach, the solid line of his body along his back. He lay still for a moment, listening.

Tyler’s breathing was slow, close to sleep. The radiator had gone quiet. A car door slammed outside; someone laughed; a bell rang for a class no one would attend.

He rolled carefully onto his back. Tyler blinked awake beside him, hair smashed on one side, eyes squinting against the light.

“Hey,” Tyler said, voice rough with sleep.

“Hey.”

“You look different,” Tyler said.

“Bad different?”

“Less… haunted.” Tyler yawned, stretching his arms over his head. The motion made a small crack in his shoulder. “How do you feel?”

Ethan thought about it. “Like I’m finally done pretending yesterday didn’t happen,” he said. “And not just last night. All of it. Eli. Mark. The whole year.”

Tyler nodded slowly. “That’s a lot to be done pretending about.”

“Yeah.”

“But you’re still here,” Tyler said. “That counts for something.”

“Barely,” Ethan said without thinking, then caught himself. “Barely counts.”

“Now you’re quoting Dr. Carroll,” Tyler said. “Impressive.”

They lay there a few minutes more, between sleep and the day, between what had been and what would come next.

“What about next year?” Ethan asked the ceiling. “You still want to be here?”

“With you?” Tyler asked.

Ethan turned his head. “Yeah. With me.”

“Yeah,” Tyler said simply. “I do.”

The panic that had been living under Ethan’s sternum for months didn’t vanish. But it had less room.

He sat up, the sheet sliding to his waist. The room looked different in the morning light, and not because of the boxes. Mark’s bare mattress, the open closet, the stack of textbooks by the door—they were still there. But they were background now, not the whole frame.

He stood, pulled on his jeans, found his T-shirt near the foot of the bed. Tyler watched him with an ease that said nothing had shattered overnight. No masks being refastened. No distance being reasserted.

“Coffee?” Ethan asked.

“Always.”

They stepped into the hallway together. No one was there. Just the long run of doors, some closed, some open to glimpses of other half-packed rooms. The building hummed around them, old and familiar.

They walked toward the common room side by side, shoulders brushing once, twice, a contact that felt as natural as avoiding it had once been.

The day would bring whatever it brought—papers to pick up, forms to sign, parties to endure, a graduation schedule taped up in the lobby.

For now, there was just this: a hallway, two mugs waiting by the machine, and the quiet fact that Ethan had decided to stay.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

🧵 Join me on Threads: Caleb_Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

🦋 Bluesky: @thecalebreed.bsky.social

Loved the interactions between Ethan and Mark and Ethan and Tyler.

Looking forward to sophomore year :)

❤️😍🫂💞❤️