Chapter XIV — The Shift

Homecoming in the Lowcountry — where the noise of Westmore fades, and what’s left is the quiet that raised him.

“The week before break hung heavy, a long exhale nobody quite finished.”

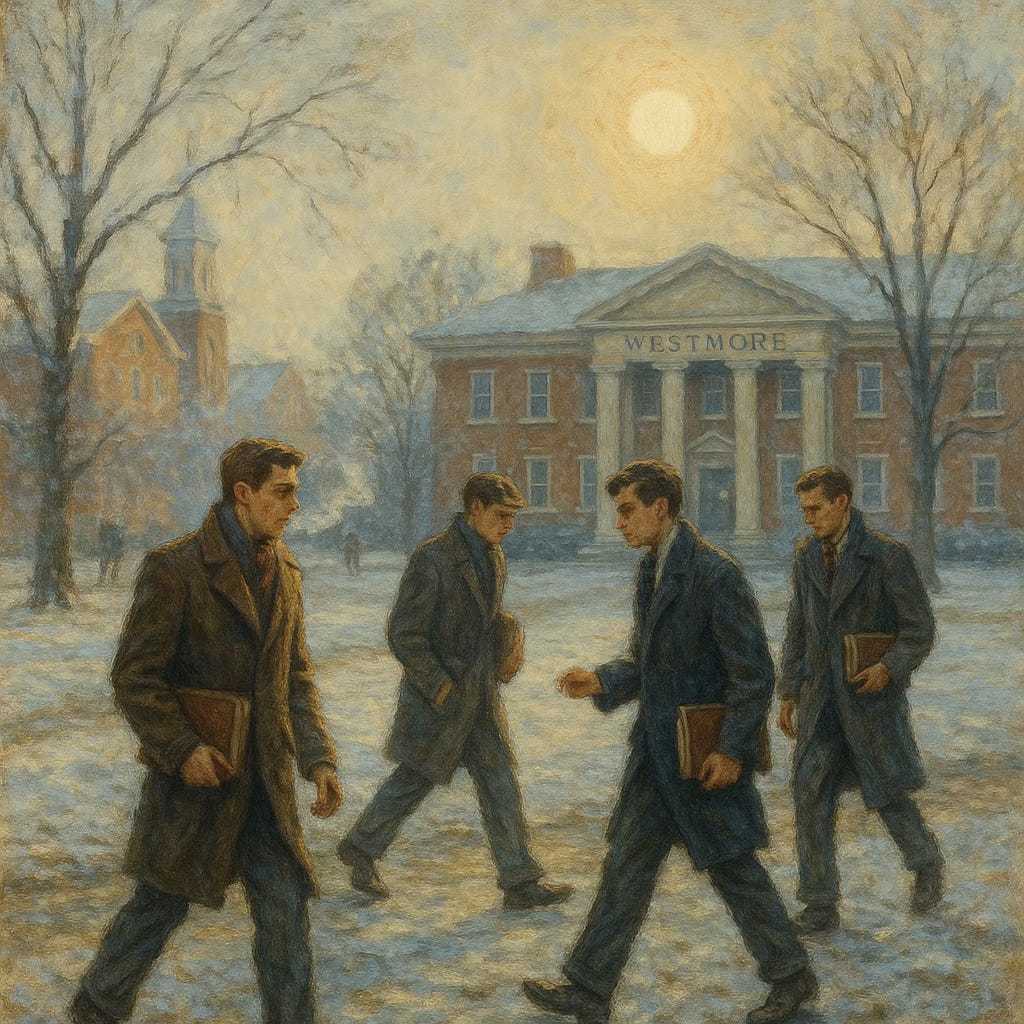

The air felt brittle, the kind that stung when you breathed too hard. Westmore’s quad was drained of color—bare trees, damp brick, a thin film of frost that clung to the steps long after sunrise. Classes were nearly done, but the college refused to exhale.

Even after initiation, the new brothers weren’t free. Clay had made it clear: “Study hall doesn’t end until grades post.”

So every afternoon that week, the six of them still filed into the library at one o’clock sharp, same long table under buzzing lights, same worn carpet that smelled faintly of dust and chalk.

Ethan sat between Connor and Teddy. Mark had already drifted toward a window seat beside two guys from chemistry—one of them tutoring him, or pretending to. The air inside the library felt heavy, soaked with boredom and fluorescent fatigue. Every sound—the scrape of chair legs, the hum of heaters—carried like confession.

Teddy clicked his pen against the table. “Feels like boot camp with better lighting.”

“Boot camp ends,” Connor muttered, face-down in his notebook.

Mark looked up from his group, grinning. “Hey, at least we’re real brothers now.”

“Yeah,” Teddy said. “Brothers in remedial biology.”

Ethan smiled faintly. He was half-listening, half drifting, watching sunlight move in slow rectangles across the table. He realized, with mild surprise, that he wasn’t tense anymore. The silence didn’t feel punishing; it just was.

By four, they were released. Mark and Connor went to the dining hall; Teddy announced plans to “study” in front of the TV. Ethan walked alone toward the bookstore, cutting across the quad where the flag barely moved in the cold wind.

Inside, the warmth hit like nostalgia. The bookstore wasn’t much—just a few aisles of textbooks, school supplies, CDs, magazines, and a counter stacked with impulse buys. The cashier, a senior named Jack who worked every semester to offset tuition, looked up from the register.

“End of the line?” he asked.

“Almost,” Ethan said.

“Good. You guys have been living in here.”

He placed his usual on the counter: one glass bottle of Arizona Green Tea with Ginkgo and a pack of Camel Lights. The bottle’s green plastic wrap gleamed under the lights, cherry blossoms curling up its side like old porcelain.

“The bottle looked like porcelain—pale green plastic, cherry blossoms and gold script pretending at calm.”

Jack rang him up. “You’re Delta Chi, right?”

“Yeah,” he said. “How’d you know?”

“I’ve seen you hanging around with Jason—he lived on my hall freshman year.”

Ethan laughed quietly, handing him his ID. Outside, the air was sharp again. He cracked the cap, the metallic ping echoing against the brick wall, and took a long sip. Sweet, cold, just enough caffeine to keep him from drifting.

Across the quad, he spotted Tyler walking out of the science building, collar turned up against the wind. He was laughing with another student Ethan didn’t recognize—a real laugh, unforced, easy. Ethan thought about calling out, then didn’t. He let the moment stay small.

Back in McClintock, the hall smelled of weed and burnt popcorn. Mark was sprawled across his bed with his Aiwa shelf stereo blaring the end of Counting Crows’ “A Murder of One,” one of the six discs stacked in its changer.

“Dude, turn it down,” Ethan said, dropping his bag.

“Finals playlist,” Mark answered, grinning. “It’s working. Barely.”

Ethan lay back, the radiator clattering awake. The semester felt like it was shrinking behind him, each sound turning faint and harmless. He thought about the porch at the house, about Tyler’s quiet grin, about Eli’s silence since initiation. All of it had stopped feeling like noise. It just sat there, like weather.

“He told himself that once finals were over, he’d feel different—lighter, maybe.”

He wasn’t sure what that meant, but he believed it.

“The Row looked like a power surge waiting to happen.”

Every house was overdoing it for the Christmas-light contest, but Delta Chi made it a mission. Strings of multicolored bulbs tangled across the roofline, nets of white lights draped over bushes, cords trailing from open windows. The sleigh Jason had pulled from the attic leaned against the porch rail, half finished, already warped by frost.

Inside, the house buzzed with pre-break energy. The downstairs stereo—an archaeological dig of mismatched components—was already thumping. Two Pioneer speakers from the eighties, a Fisher amp with no knob, and a Technics six-disc changer blinking its random order like an SOS. The stack perched on milk crates, cords running through the baseboards.

“The house stereo was a patchwork of ghosts—every brother who’d graduated left a speaker or some component behind.”

Mark and Connor were stringing garland around the bannister. Teddy had rigged a strand of lights along the bar that shorted every time someone poured a drink. The smell of bourbon and cigarettes blended with pine and old carpet.

By late afternoon, the Kingston girls had arrived, Catherine leading the charge in a green sweater and boots that clicked on the hardwood. The noise swelled instantly—laughing, music, the pop of beer caps. Eli was with her, a cigarette tucked behind his ear, running on that effortless charm he slipped into like a jacket.

When Ethan passed them in the hall, Eli’s eyes caught his for half a second—recognition, apology, habit—then the moment was gone.

Jason’s voice cut through from the porch. “Hey, Harris! Fuse blew again. Grab the ladder.”

Upstairs, Jason’s room smelled faintly of cedar and cold air. The lamp on his desk flickered as they rewired another strand.

“Festive enough?” Ethan said.

“Festive enough to kill us,” Jason replied, twisting a plug until the lights snapped back to life. He lit a cigarette, exhaling toward the cracked window.

“You’re alright, Harris,” he said finally. “Don’t let the rest of them make you think otherwise.”

Ethan nodded. He wanted to thank him but didn’t trust his voice.

Downstairs, Found Out About You bled through the speakers, the volume distorting the bass. Teddy declared it the “song of the semester.” Connor argued that Hey Jealousy had more range. The argument became a chant, a cheer, then dissolved into laughter.

“The house shook with the kind of laughter that only happens when everyone knows they’re leaving tomorrow.”

Catherine had taken over the couch, gesturing wildly as she told a story. Eli leaned close, listening too carefully, smiling just enough. When he laughed, it was the same performance Ethan had seen all semester. It didn’t sting anymore—just looked exhausting.

Later, Ethan slipped outside to cool off. The night air bit through his shirt. On the back steps, Tyler sat smoking, shoulders hunched, smoke curling in front of the colored lights.

“You heading out early?” Ethan asked.

“Soon as I wake up. You?”

“Six-hour drive. Home by dinner if the Jeep makes it.”

“Better bring a tape deck for when the Discman skips.”

Ethan laughed softly. “Already does.”

Tyler held out the cigarette. Ethan took it, the filter warm from his lips. They shared a quiet drag, watching the lights flicker across the lawn.

“It wasn’t tension anymore. Just understanding.”

“Take care of yourself,” Tyler said finally, voice even.

“You too.”

They stood. Ethan brushed ash from his sleeve, nodded toward the noise inside.

“See you next semester.”

“Yeah,” Tyler said, smiling. “You will.”

Ethan walked across the quad later, the house glowing behind him like a postcard. The noise had faded to a hum, red and green light blurring into white.

“The movement felt like a pause—an interval between lives.”

He left before dawn, frost crusting the Jeep’s windshield. The Discman balanced in the console, anti-shock long dead, a Counting Crows CD skipping every time he hit a pothole. The MapQuest pages sat folded on the passenger seat, six sheets curling at the edges from the heater vent. He’d printed them in the computer lab the night before—bold black text, capitalized turns, LEFT ONTO US-460 EAST—directions that looked more official than they were.

The bottle of Arizona Green Tea rode between the seats, the fake-porcelain design gleaming faintly in the dash light. The sweetness clung to the back of his throat. Cigarette smoke slipped out the cracked window, vanishing into the cold.

“He kept replaying the same track, even though it skipped on the chorus. Maybe he liked hearing what was missing.”

By the time he hit the highway, the sun was up—a flat, white light bleeding across the fields. He passed trucks hauling Christmas trees, the scent of sap leaking through the air vents. The road unrolled in straight lines east, toward home, toward quiet.

He thought about Tyler’s cigarette ember in the dark, about Eli’s practiced laugh, about Jason’s voice at the window. None of it hurt; it just hovered, like static on an old radio.

Around noon, he stopped at a gas station off I-95. The asphalt shimmered faintly with salt. He bought another bottle of the same tea, cold enough to fog the glass, and a bag of Combos. The clerk barely looked at him. He liked that.

Home appeared mid-afternoon, crossing the Black River, then the Waccamaw, the marsh stretching silver under a low winter sun. Finally, he was home.

The closer he got to the coast, the flatter the light became. This stretch of the state still looked untouched if you didn’t know better—tidal creeks winding through spartina, pines giving way to live oaks. He knew every curve. His family had been out here since the first houses went up, long before the golf course and the security arm. Moving out here had been its own kind of announcement back then: proof that you’d made it.

He slowed at the gatehouse out of habit, though the guard still leaned out and yelled for him to slow down. They’d been doing that since he first started driving—same guard, same bark, as if every kid who grew up here was destined to test that curve. Out of sight of the gate, he did what he’d always done: dropped a gear and gunned it over the sweeping bridge, the Jeep rising just enough to feel it in his stomach. The salt pond, covered with ducks, spread out on the left, the creek glittering on the right, the ocean a straight shot ahead beyond the dunes. If the security truck was parked at the gate, you were safe; it meant the patrol was inside, nowhere near you.

Beyond the bridge the road curved beneath live oaks, their limbs knitted together like an archway. Half the houses were lit again—North Carolina and Virginia plates in the driveways, families back for the holidays. His parents were part of the year-round crowd, the first wave who’d bought when the roads were still sand and rumor. The rules hadn’t changed: no colored lights, no noise after ten, no sign of effort. Effort, like money, was meant to look inherited.

Out back, the old johnboat was still tied to the same piling, paint worn to silver along the gunwale. His father had been running that boat since before the developers broke ground—knew every bend of the creek by smell. When Ethan was a kid, they’d go flounder-gigging after dark, the motor wide open with no light, his father navigating the sandbars and oyster beds by memory. Folks used to follow him from the landing just to see where he’d fish, but they never found his spots. The new people out here were all performance: glossy gear, spotless boots. His father never had to prove a thing.

The house could have been in one of those southern design magazines his mother loved. She had spent weeks making garlands, swags, and wreaths from the cedar, magnolia, and pine from the yard—everything finished off with an oversized red-velvet bow. It was a tasteful representation of the classic Lowcountry Christmas. This wasn’t the type of place to hang Christmas lights.

His mom was in the kitchen, potpourri simmering on the stove as she finished rolling her Christmas cookies in powdered sugar. “Why didn’t you call from the road?” she scolded. “Your daddy and I had no idea what time you would get here.” Ethan returned her embrace and kissed her cheek.

“I wish you wouldn’t smoke,” she said. “It’s so tacky.” He wanted to remind her that she was the only one in her family who didn’t smoke, but it wasn’t worth it.

“Get settled,” she said finally. “Your daddy took the dogs down to the beach, and your sister should be home from school any minute.”

Dinner was harmless—grades, classes, the house. He told the safe version: that the lights contest was a disaster, that they’d still won somehow, that Jason had nearly electrocuted himself. They laughed, and for once it didn’t feel like pretending.

He’d grown up between two kinds of perfection—his mother’s, measured in ribbon and polish, and his father’s, measured in quiet skill. Everything about the man seemed certain: how to back a trailer in one try, where the trout would be after a storm, what silence was for. That certainty had always been Ethan’s map for what a man was supposed to be. Maybe that’s why Westmore had rattled him so deeply; he’d been looking for that same steadiness and kept finding performance instead.

That night, in his old room, the posters still hung where he’d left them—Pearl Jam, Pulp Fiction—corners curled from humidity. He lay back, listening to the ceiling fan’s lazy churn, and realized how quiet the world could be when no one was demanding anything of him.

“He realized how quiet the world could be when no one was demanding anything of him.”

The next morning he walked down to the dock. The tide was low, the pluff mud shining gray beneath a thin sun. The air smelled of salt and sulfur. He sat on the edge, hands deep in his jacket pockets, listening to the creak of boards and watching the fiddler crabs looking for food.

Across the creek the new houses had their docks lit up like runways, a glow that didn’t belong to the water. His father never needed lights. He and his brothers had grown up hunting and fishing these creeks their whole lives, long before the gates and the golf carts. The new people called it lifestyle; for them it had just been life.

It struck him that the quiet wasn’t emptiness anymore. It was space.

He skipped a shell across the surface—one, two, three hops—before it vanished. Behind him, gulls cried like they were fighting over something invisible. Just beyond, he could see the back fin of a spottail bass tailing in the shallows, rare this time of year. He watched the spottail’s fin cut the surface and disappear again. You only saw them tail like that in places the world hadn’t ruined yet.

He thought of the semester like a weight shed: Eli’s masks, the noise of the house, the blur of pledging. All of it still existed, but it no longer owned him.

“The quiet wasn’t emptiness anymore. It was space.”

Further Reading

If you like this series and are curious about books that have inspired me, I’ve curated a collection on Bookshop.org. Buying through that link supports independent bookstores—and it helps sustain this project.

Stay Connected

📖 Subscribe to Caleb Reed for weekly chapters and essays.

📸 Follow along on Instagram: @caleb_writes

🧵 Join me on Threads: Caleb_Writes

📘 Facebook: Caleb Reed

Nice to see Ethan away from campus